Bleeding for Jesus: John Smyth and the Cult of the Iwerne Camps

Andrew Graystone, Darton, Longman & Todd, £12.99

KEN BELL winces through a sad story of sadistic abuse and cover-up

John Smyth QC had a public image in the 1970s and 1980s as a conservative activist who worked with Mary Whitehouse in her failed campaigns to hold back the twentieth century. He lived near Winchester College, and was well-known there as a senior figure in the Iwerne Trust, which recruited young men to Evangelical Anglicanism. John and Anne Smith often entertained boys from the college at their home, and Smyth became known as a man who would openly discuss matters that troubled the budding Evangelicals. Masturbation was one, and the need for a man who has given himself to Christ to suffer for his sins was another.

You can see where this is going, and sure enough it made a marvellous cover for Smyth, a moralistic homoerotic sadist who used his position to take youths and young men to his garden shed, order them to strip naked before administering ferocious canings to their bare bottoms. As part of the ritual, Smyth was also naked, and lotion was helpfully kept on a side table which Smyth used to soothe the ravaged backsides before putting the victim into adult nappies so that the blood after a caning of up to several hundred strokes would not stain his trousers. Then the fellow would be sent off to the house, for a nice cup of tea from Anne, who would offer him a cushion to sit on. Smyth had thoughtfully soundproofed his shed and a small pennant was stuck in the garden as a sign to Anne not to approach.

On one level the story of John Smyth and his predilection for BDSM is yet another account of an older, upper-class, closeted homosexual getting his rocks off with younger men. There is no suggestion in Andrew Graystone’s account of anybody being coerced, and neither can Smyth be accused of paedophilia, as none of the submissive participants were pre-pubescent. However, it is always the cover-up that is important with these matters, and the concealment of Smyth’s activities involved rather a lot of people who did an excellent job of keeping a lid on the story for many years.

Smyth looked for participants amongst the older pupils at Winchester, which was an inspired choice as the school, according to Graystone, comes over as a closed world where what happens in the school stays in the school. The pupils speak what amounts to a cant tongue, where words that are really only known to the initiates are used; thus homework is called ‘toytown’ and bicycles are ‘bogles,’ to give just two examples. The whole institution seems to operate with its own ‘complex and arcane culture’ that had been handed down the generations with its original meanings probably long forgotten but which were adhered to religiously. New pupils were tested at the end of their first term on their grasp of the cant, and any who failed could often expect a dose of the cane to encourage further study.

His chairmanship of the Iwerne Trust allowed him to recruit volunteers for the rod from a wider field than just Winchester. The trust ran summer camps to provide intense religious training in Evangelicalism and entry was restricted to pupils at the elite public schools. The aim of the camps was to take tomorrow’s leaders of Britain and ensure that as many as possible became Evangelicals. John Smyth must have been in his element.

Eventually, of course, the complaints about Smyth’s activities began to mount, but incredibly enough, all the complainers did was contact the senior figures within the same Evangelical sub-section of Anglicanism that was part and parcel of the problem. A gaggle of fathers descended on Winchester College to demand that something be done, but at the same time they insisted that whatever was done had to happen quietly.

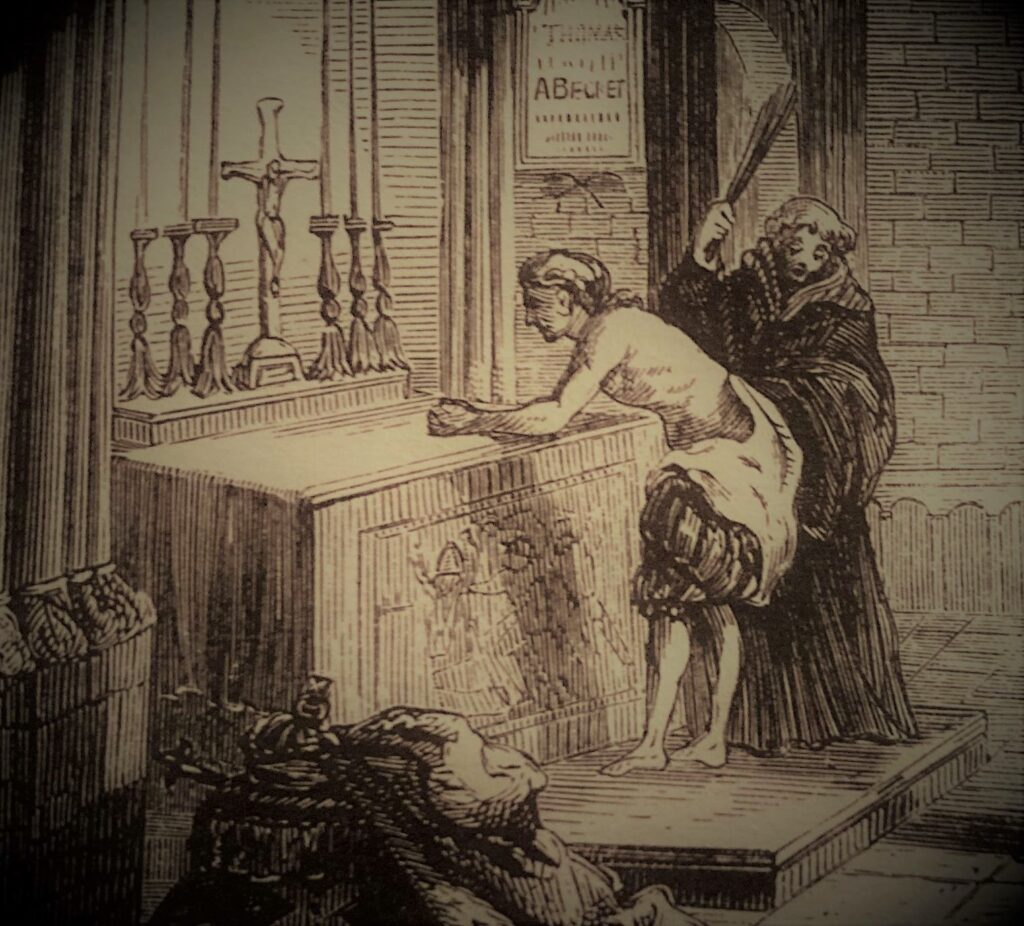

A report on Smyth was prepared in 1982, which runs to twenty-two short paragraphs, and sets out succinctly what he had been up to. This report was then hidden away and only shown to a few senior Evangelicals. Its author, Mark Ruston, was very concerned that Smyth’s activities may have been heretical. In particular, he believed that the canings strayed dangerously close to ‘a flirtation with Popery,’ owing to the obsession with ‘penance’ and it seems to have been that theological concern, rather than the BDSM dungeon that Smyth had created out of his garden shed that was the most troubling.

The headmaster of Winchester College banned Smyth from the premises, which mollified the fathers at least. The Evangelical capos concluded that Smyth was in error theologically, and that issue could be corrected quietly. Smyth helped the process along by taking his collection of canes and nappies into the garden and making a bonfire out of them.

Finally, the Iwerne Trust arranged for Smyth and his family to move to Zimbabwe in 1984 with a special trust fund to cover his living expenses. There, he pretty much carried on as before only this time with African youths rather than English ones. Eventually, the heat became too much in that country, so he scampered off to South Africa and there continued in his old way until the local church expelled him. By 2018, with the story having finally broken, he very conveniently for all concerned died of a heart attack in Cape Town.

This fairly unpleasant tale is not really about Anglicanism or its Evangelical sub-section. It is actually the seemingly endless story of upper-class abuse, the sense of entitlement that those people have and the code of omerta that governs it all. By helping to break the story, Andrew Graystone has helped to shed some light into the activities, mores and attitudes of our country’s rulers and the state that exists for their benefit. That, finally, is a very good thing indeed.

KEN BELL is a Mancunian who fetched up in Mexico, and who now lives in shabby retirement in Edinburgh. He writes as a hobby in his twilight years; a fuller biography can be found at his Amazon author page

All good stuff and on the ball, thanks Ken. May I, as an Old Wykehamist who had the misfortune of being taken out by the Smyths a couple of times for Sunday lunch at their house in the late 1970s, fortunately with no beatings or ill-effects (a failed grooming, as I found the guy exceeedingly creepy), make the following corrections?

It’s “toyetime”, not “toytown” (“toyes” were small cubicles in which boys did their homework in their boarding houses); and second, the test on the Win Coll argot, known as “notions”, took place after two weeks in the first term rather than at the end of term. Given that there were 600 or so words and phrases to learn, as well as a number of idiotic ditties and rhymes, this was, to use contemporary parlance, “quite the ask”. I don’t recall anyone being caned for failing the test; you just had to do it again. Indeeed the cane was brought out seldom at Win Coll. See further recollections I’ve made regarding the culture of this school and otheres under the handle “Anon” at http://survivingchurch.org/2021/09/06/bleeding-for-jesus-martin-sewell-reflects/