LIAM GUILAR‘s epic of post-Roman Britain enters its eighth chapter

The Story So Far (Chapters 2-7 inclusive have all previously been published on this site, starting here). The complete poem will be published as A Man of Heart in 2023, by Shearsman.

Mid Fifth Century Britain. After the legions have withdrawn, the island is facing civil war, a growing number of external enemies and a steady tide of pagan migrants looking for land.

Vortigern has been appointed to protect what’s left of Roman Britain. Following standard imperial practice, he has employed Saxon mercenaries led by Hengist. Together they have defeated the immediate threat of an army of Picts and a Northern rebellion and stabilised the province. Vortigern has married Hengist’s daughter.

Part two begins with Vortigern leading the Field Army towards a meeting of the Northern Lords, hoping to convince them that a unified province is in their best interests. The precarious balance of power he has established is about to be destroyed.

1

Damp woollen clothes,

the itch and stink of them,

never dried, except when smoked

acrid by the heat of a fire.

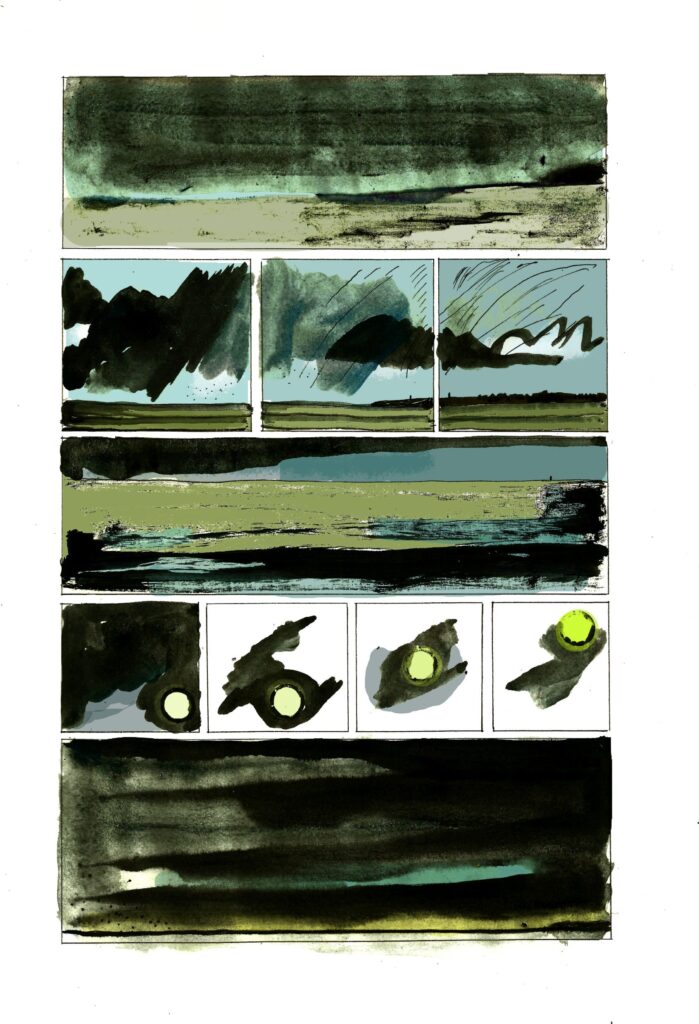

Rain falls, drifts, batters,

the wind skins the rocks

or drags mist from the hollows

while the clouds smother the hill tops.

Ragged local guides thread

the mounted column

through unmapped valleys.

Occasionally the mountain wall

greyer than the clouds

curves the northern horizon.

Riders keeping below the ridge,

following the main party.

Like guilt, thought Vortigern,

not enough to stop his progress;

a persistent qualification

intent on being noticed.

Confrontation seemed inevitable.

He rode towards it.

The lead rider, Hengist’s latimer,

dismounted, knelt and greeted him.

The second removed the gilded helmet

shook out her hair and said:

‘Wæs hæilVortigern Cyning.’[ii]

The drab hillsides patched with torn cloud,

the finest of drizzle-intensified colours,

the brown horse, the green, rain darkened cape.

Her hair, like dull gold, shaking loose.

Hengist’s delighted chuckle.

A sound so rare,

he turned to see who was behind him.

Dull gold of her hair.

Finger tipping an impossible softness.

He claws for his mind but undressing

a marvel

green eyes

watch

like a diver

assessing the risk

before

committing herself to gravity.

Fingertipping, soft

a marvel but

it’s cold here and the escort is waiting.

Green eyes

wide open, watching?

‘Lauerd king wæs hæil;

For þine kime ich æm uæin.’

It’s cold here and the escort is waiting.

‘This is no place for a Queen.

I left you safe, with your uncle.

We ride towards a confrontation.

Go home.’

‘My home is with my husband.

I have come to see the lands you gave me.

You are riding I think to a council,

a gathering of the northern tribes.’

‘Go home, lady.

This is no fit place for a Queen.’

He turns back to the valley floor.

The riders follow,

keeping just below the ridge line.

Like guilt, he thinks.

The column camped beside dark water.

He approved the choice of ground,

checked there were skirmishers along the heights,

made sure the baggage train was safely in,

waited for the rear guard to arrive.

See him talking with his officers,

noticing their discipline

making time to hear their stories,

in the bustle of the camp,

where behaviour is defined

as clearly as the perimeter

he rides out to inspect,

ignoring the presence

dragging at his attention.

Tents pitched, guards posted,

before the light began to fade

he wandered through the lines,

through the susurration

of tired conversations

stopping to talk to weary riders

commending them on the care

they gave each other, their arms and horses.

His world, where he was most at home,

contaminated by their shadow,

stopped on higher ground,

erecting simple shelters.

She sits beside the latimer

watching the busy camp below.

‘I stopped counting things I’d never seen before.’

‘There were too many?’

‘Yes. The way

water spills from the cliff top and wavers as it falls.

Clouds and birds below us, in the valley.

My uncle hates mountains,

says they remind him of a heaving sea.

What is the best word to describe

how stray clouds drift across the hillside?’

‘Drift is good.’

‘They remind me of assassins.’

‘In daylight?’

‘Not all assassins wait for darkness.’

Small figures

scrambling towards them,

become Vortigern

and his guard

slithering in the scree.

Keredic removed himself.

A man can turn a hill into a mountain;

an evening stroll into an epic climb.

From the valley floor

he could see a band of rock,

her tethered horse cropping the grass,

the shadow of a cave.

Then the damp fog became the world.

Smooth stones skittering behind him,

stalled in a dreamlike lack of progress.

She was sitting inside the cave.

She did not rise or greet him.

‘Lady. This is not wise or safe.’

‘Not safe? Here?

In the green world, in the wind and rain.

There are no dangers here that can’t be faced.

But stranded in a hut, hedged

by brutal threats and body parts?

No reason to greet the day

or welcome the night?

This is not safety but burial,

alive, behind locked doors

until the stallion calls to rut.

I am not ‘Hengist’s daughter’

live bait to trap a wary fox.

I am myself. And I chose you.’

When he had finished,

she waited for him to leave

but he lay beside her,

on one side of the causeway

looking to the mythic landfall

on the other side.

He had heard the stories

of the cottage in the woods.

A stand of body parts

and heads that shrieked

if anyone approached.

What had she recognised in him?

He had done nothing to earn

this devotion.

2.

The rain intensifies.

A man is speaking quietly,

someone laughs.

Keredic is singing.

His song sounds older than the rocks.

She is no longer Hengist’s daughter.

Or the wife of Vortigern the King.

She is like rock, tree or river,

as certain as the mountains

and as patient, waiting

for his act of recognition.

Half way across, and no more stones.

He can go back, he’s always done before.

Rise, fumble for his clothes.

Or he can brave the distance to the other side.

If it’s a choice?

A man stands in the cathedral ruins

looking at the sky.

The bombed reality softened by a memory

of upright walls, unbroken roof.

Even if ghosts and stray dogs

scuffle in the garbage

he can remember people in the pews,

the drift of sacred music,

the certainties of ritual.

Easier to live here,

where the shattered past

still feels like home than leap into a world

that’s blank and waiting to be born?

No maps, no rules, no precedent.

When a Queen rides, armed, in the wilderness

this is an unimagined world.

‘Lady, may I stay with you tonight?

And tomorrow, would you ride with me?’

They say: her smile is like the sunrise;

the slow spread of light and promise

after the horrors of the night,

but she never smiled at ‘them’ like this.

And later, she says, ‘But tomorrow night

we find a bed with fewer stones?’

3

Teetering over the river

the complex was scattered,

across the flat hill top

like bad teeth in a jawbone;

great hall like a strange squat wooden tent

with a scattering of huts

surrounded by a ditch and palisade.

A growth on the land,

like hanging smoke,

beside a barrow

where the ancestors slept.

A chaos of temporary shelters

festering down the slope;

banners and stacked spears,

horses, mules, carts.

Men clustered around small fires,

watching as they pass.

After days in the dripping quiet of the hills,

they were ambushed by noise and movement

crashing the private space she had begun to craft.

The bellowing of slaughtered cattle.

Carpenters hammering and sawing

as huts went up to hold guests;

the smiths at work. Everyone

with a job to do and a place to be

swirling them into public routines.

She watched the Lords accumulate to greet him.

Then he was gone, as though the sea had surged

and dragged him off the beach into the rip

that sped him out towards the sky line

leaving her bereft and stranded.

Wives and daughters came to greet her,

took the bridle, set off in procession,

leading her towards an isolated hut.

Slaves brought silver bowls

with steaming water,

sweet smelling oils;

the women bobbed and fussed,

admired how beautiful she was,

then left and closed the door.

Next day, in the great hall,

Vortigern accepted homage,

dispensed gifts, discussed plans,

handed down judgements.

Alone in a hut that smelt

of smoke and fresh cut timber,

she was prowling from wall to wall.

Dressed in the finest silk

provided by their hosts,

hair dressed, jewels shining,

a predatory goddess

no slaughter could appease.

The silver dishes

scattered to the corners,

fine white towels thrown across the room,

the servants fled in terror.

She was waiting for the horns

that would summon her to the feast

when Keredic entered

to escort her to the hall.

Wall hangings flicking the firelight.

A tripod burning something fragrant.

No loom, no Mother Gothel.

I will hone my knife and hunt him down.

‘If I am Queen: this is my country?

Should I not be there when they discuss its future?’

Impossible to explain,

not one man in ten thousand

would have taken her to the gathering

and of that number, not one in a million

would have listened to a word she said.

‘Twenty four paces from hut to hall?

The door shut and guards all round.

Twenty four paces from where I should be.

I might as well be stranded on an island

staring at the cliffs and cut off by the tide,

locked here until he wants to fuck

his princess titznkuntnhair.’

4

If you were listening,

you could hear Dame Fortune

spin her wheel

and smile.

‘Chieftain,’ said his host,

‘God smiles on you.

Lords of the North,

retinues like honed blades

ready for war,

secure in their indifference

came here to talk.

Bishops and book-learned men

recording their agreements.

3 weeks, and not one death.

You have sold them an idea:

the priest safe with his flock,

the famer will go to his field,

the merchant to the market.

Ships bringing goods to our ports

and our roads busy with trade.

Chieftain, you are truly blest.

3 weeks we’ve feasted.

The bards of the north

have come to compete

for praise and honeyed mead.

Magnificent stories,

music to gladden the heart

and the last three nights

your wife as my companion at the table.

On God’s wide earth she has no match

for wit and wisdom. She knows

more stories than my poet.

Tells them better too.

No wonder men will follow you.’

Commotion at the gate.

First the messengers. Then the refugees.

Confusion, contradiction, disbelief.

Vortimer had slaughtered Hengist’s men.

Britons had crowned him King.

Horsa was dead. Vortimer this,

Vortimer that, massacre and murder.

Saxons hunted like wild pigs.

A bounty of ten silver coins for every Saxon head.

Its weight in gold for Hengist or his daughter’s.

Slack mouthed the heads still speak:

This will be our second child…on a stick;

We were desperate, we were lucky…on a stick;

He’d go off to work, and then come back…on a stick;

If a man steers clear of strife, his children have a chance….on a stick.

Those considered loyal had died.

You’re the best man for the job.

The house smashed, the bodies…on a stick.

Pogroms and purges and a rising body count.

Vortigern thinking he had underestimated his son

until the name of Gloucester or his men

were noticed in every successful action.

But what was he doing? Vortimer, upright Christian boy,

exasperated by the heathens, wanting to protect his church,

deluded, predictable. But Gloucester

had both eyes open and could see

this was a war he couldn’t win.

The last messenger to arrive knelt before his King.

‘Speak up man, we do not punish the messenger for the message.’

But he muttered on, so Vortigern leant forward

and they all heard the oath,

saw the blade, saw him lunging for the King.

The host leapt between them.

Hengist’s seax stabbing the assassin’s throat.

Both men fell; Vortigern unhurt.

Rowena entering, breathless,

as the corpse was dragged away.

The assassin’s knife had skidded

off the King’s mail shirt

and pricked the host’s arm.

‘The knife is poisoned,’ said Rowena,

who knew about such things.

‘Lord,’ she said, ‘you have my gratitude

but find a priest and come to terms

with whatever God you worship.

You will be dead before the sun sets.’

Saxons preparing to ride, grim and resolute.

Experts in the rules that govern vengeance.

Rowena standing by her father, dressed to travel.

Despite the foul weather, there are ships beating north,

to risk the crossing and take them home.

As his world unravels.

Hengist making plans, seeing the scale of the disaster.

‘I will return with fifty ships of first rate fighters.

I will avenge my people and this insult to your rule.’

Vortigern walks the perimeter.

The short day is coming to an end.

His men are waiting his instructions.

The northern lords are waiting for instructions,

already wondering if they can be ignored.

There are no answers in the landscape.

It is as dull and littered as his mind.

As blank as the coin he’s turning in his hand.

All year watching Vortimer, Gloucester and their friends.

Sifting rumours of revolt, looking for sinew under insolence.

But the rebellion should have happened late in summer

or in the early spring next year. When the summer faded

they’d left Horsa on the coast, in striking distance

of any army mustering in the south. How could

he have been so wrong? He walks amongst the details,

picking over the pieces, asking why the building fell.

Since he was old enough to understand

he knew one day would find him:

Shipwrecked, broken and alone.

But that was not today.

This was another problem he could solve.

He had stumbled to the clarity beyond,

like the survivor of a shipwreck,

washed overboard,

surprised by solid ground,

looks back to see the surf that trashed him,

doesn’t break the skyline

and his tattered ship’s still floating in the bay.

He still had the field army.

They had no need of Hengist

to trash a mob of lordlings

and their reluctant, ill-armed tenants.

And he hadn’t been alone.

Trust someone because he can,

not because he has to?

In what language do those words make sense?

Dixit Dominus Deus

non est bonum

esse hominem solum

faciamus ei

adiutorium similem sui.[iii]

The sentry on the wall

will swear he heard the Thin One

repeat a Latin phrase

then laugh.

He lies of course, there was no laughter.

‘And I will make an help meet for him.’

It is easier to say ‘he laughed’

than accurately describe the small sound

a stranger made acknowledging

that understanding is redundant

when it’s delivered past its use by date.

5

Rowena sitting straight backed

staring at her fire.

We see her from behind.

Then her face in profile

as the sound she’s waiting for

breaks.

Vortigern straightens,

entering the room.

Stalled. Baffled. Wondering.

She rises. ‘Oh foolish man,’

she says, seeing his surprise,

‘when will you ever learn?’

The sound of a door being closed.

Perhaps he managed,

‘I watched you leave’

or, ‘I’m so sorry.’

An awkward blur of mouths,

hands, her hands, his hands, hard to tell.

Nose to nose,

he asks the golden lady,

‘What would you do?’

She had waited for this door to open.

But now the gate’s swung wide,

invited in, she pauses on the threshold;

‘I can taste winter; smell it on the wind.

Ice darkens the edges of puddles,

the thick mud hardens into rut and fold

and the wind tests the walls.

Outdoors everyone has begun to hurry.

The space from dwelling to hall becomes an ordeal.

Soon only the numbed sentry,

counting the cursed hours of his watch,

will stay squinting into the hazed light,

knowing no army moves in winter.’

‘Gloucester knows the northern winter.

He was trapped here on The Wall,

searching for his legion.

We’ve all heard his snowbound stories;

roads they had to swim across,

mud so deep men drowned in it.’

‘They were impatient,

their timing is inept.

Why are you smiling?’

‘Because incompetence is unpredictable.

They went too late or far too early.

The gods look down,

indifferent to our careful planning

and give their blessings to stupidity.’

‘I would go deep into the hills,

find a place we can defend

with half the men we have.

Then wait for Hengist to return.

And if I couldn’t find that place,

I’d build it, quickly.’

‘They‘ll expect us to go north.

We will go south and west and then

prey upon those who have betrayed us.’

‘We’ll plague the sleeping lords,

drunk by their cosy fires.

Burn their homes, steal their cattle,

kill their friends and families

and then come spring,

with Hengist’s help,

brush the remnants off the map.’

Vortigern called his officers together,

explained the friends and places lost,

named those who stood beside them.

‘You have been loyal. Now,

we travel to high country,

hard travelling, constant vigil.

From the mountains in the west,

we will fall upon the rebel lords,

we will reprimand their insolence.

They will learn the price of disobedience.’

The northern lords knelt before him.

‘Send for us when you are ready:

we will ride beside you.

Take our sons as hostages and guides.’

Local guides thread the column

through unmapped valleys.

The mountain wall

greyer than the clouds

leans forward to embrace them.

[i] Old English Cwēn meant both ‘woman’ and ‘queen’.

[ii] Cyning, Old English for King, is pronounced ku-ning.

[iii] From The Vulgate. Genesis 2:18: ‘The Lord God said, It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him an help meet for him’

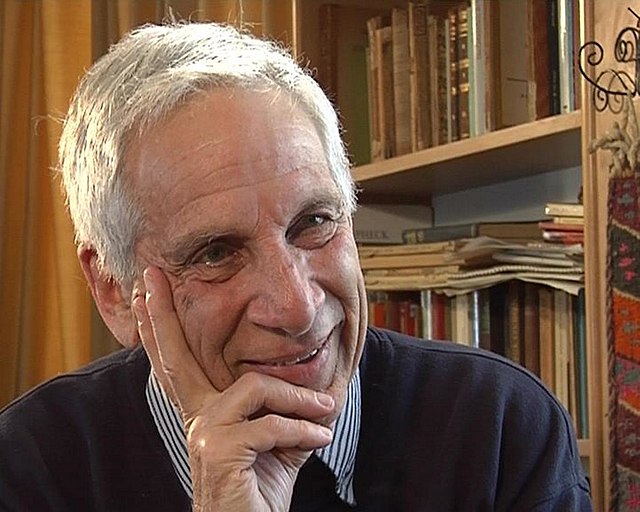

LIAM GUILAR is Poetry Editor of the Brazen Head