CHRISTOPHER SANDFORD looks back at an astonishing and controversial career

Temporal landmarks may be purely arbitrary and exist only in our heads, as Einstein and his crew tell us, but it surely still comes down to a case of tempus fugit in the matter of the Rosemary’s Baby director Roman Polanski. Turning 90 on 18 August 2023, he’s seemingly gone from being cinema’s perpetual enfant terrible to its grand old man, albeit with some significant growth pains along the way.

As often noted, Polanski’s own life has the makings of a Hollywood drama, if one with some distinctly noirish twists. His mother Bula, four months’ pregnant, was killed in the Holocaust, and his father Ryszard survived nearly three years in a German death camp. Polanski himself escaped the Nazis, but then spent the rest of his early life under Stalin’s jackboot. He eventually made it to freedom in the West, only for his wife Sharon Tate, also pregnant, to be brutally murdered in the couple’s Los Angeles home in 1969 by members of the so-called Manson family.

That might seem quite enough shadow for one life, but more was to come. In March 1977, Polanski, who was then 43, took a 13-year-old girl to a house in the Hollywood Hills to take photos of her for a magazine. Once there, he gave her champagne and tranquilizers, had sex with her, drove her home, and the following week was arrested. Polanski absconded from court on the eve of his being sentenced a year later, apparently in the belief that he was about to be locked up for life. As a dual Franco-Polish citizen, he was able to settle in Paris, where he remains at liberty to this day.

Before moving on, just a brief note on the judicial proceedings against Polanski in re. his statutory rape of a minor, which these days is increasingly portrayed – not least by Polanski himself – in almost Kafkaesque terms, and more particularly as a case of a vindictive and senile judge – one Laurence J. Rittenband, then aged 72, who presided over the Superior Court in Santa Monica, California – seeking to make an example of the ferret-faced, foreign-born sex predator standing before him in the dock.

Rittenband, it should be noted in this context, already had a long and not undistinguished legal career spanning some fifty years at the time Polanski first entered his courtroom. Of a modest background in Brooklyn, New York, he’s agreed to have been knowledgeable and personally unassuming – in one account, ‘not one of those judges who always thinks he’s in the movies’ (although by the same token, also not above keeping his own press cuttings file). In his memoirs, Polanski implies that Rittenband was star-struck by the 1977 proceedings, and, after initially exercising due judicial restraint (setting the defendant’s bail at a modest $2,500, and even allowing him to travel outside the country ‘should he so wish’), was ‘clearly over-enjoying his first excursion into the limelight.’

This account is not quite fair. In fact by the time he met Polanski, Rittenband had already presided over a host of high-profile Hollywood cases, including Elvis Presley’s divorce, Marlon Brando’s child-custody battle and a paternity suit against Cary Grant. Nor could it be concluded from these proceedings that the judge was in any way prejudiced against his celebrity defendants. In the case of Grant, for instance, Rittenband had made the eminently sensible suggestion that both the actor and the alleged mother of his child submit to a blood test, ‘after which we will determine what to do.’ When the woman in question had failed to appear for her scheduled test, and for two subsequent appointments, Rittenband curtly dismissed her suit. As well as being a stickler both for the letter and the spirit of the law, regularly advising plaintiffs and defendants alike of the need to be ‘decorous’ and punctual in his court, the judge was impressively well read in a variety of fields, which enabled him to make pertinent and original connections in his rulings. Regarding Elvis, for example, he quoted Jonathan Swift, observing to the charismatic but modestly educated ‘Hound Dog’ singer that ‘Censure is the tax a man pays to the public for being eminent.’ Looking back on the Polanski case years later, Rittenband puckishly told the press, ‘It reminds me of a line from Gilbert and Sullivan: “I’ve got him on my list.”’

Three final things need to be said about the morals rap that has effectively defined the second half of Polanski’s life.

First, there was – and in some quarters, remains – a certain amount of doubt as to whether the then-widowed director had been fully aware of his victim’s age at the time he had sex with her. It’s true to say both that the child in question, Samantha Gailey, looked significantly older than thirteen, and also that she wasn’t perhaps the naïf widely portrayed by her defenders. In her own Grand Jury testimony on the matter, Gailey noted that she had had sex twice in the year before she met Polanski, that she had been drunk, and that “yeah, once I was under the influence of [drugs] when I was real little.”

However, it should also clearly be noted Gailey was still then a seventh-grade schoolgirl who “had a Spider Man poster on the wall and kept pet mice,” as she recalled in a magazine interview. Born on 31 March 1963, she was fully four years under the age of consent then required by the state of California. Polanski was later asked by the prosecuting attorney in the case how old he had believed his victim to be when he met her. “She was 13,” he said.

Next there’s the salient point of whether Polanski had in fact raped the child, or, conversely, whether, as he later insisted, she had been a ‘not unresponsive’ partner in the act. This is what Gailey had to say on the matter when questioned at the time in front of the Grand Jury:

Q: After Polanski first kissed you did he say anything?

A: No.

Q: Did you say anything?

A: No, besides I was just going, ‘No. Come on, let’s go home.’

Q: What was said after you indicated that you wanted to go home when you were sitting together on the couch?

A: He said, ‘I’ll take you home soon.’

Q: Then what happened?

A: Then he went down and he started performing cuddliness.

Q: What does that mean?

A: It means he went down on me or he placed his mouth on my vagina.

Gailey was asked whether either party had said anything following that point.

‘No.’

‘Did you resist?’

‘A little, but not really because … ’

‘Because what?’

‘Because I was afraid of him.’

Finally, there’s the belief, still widely in vogue today, that Polanski had been railroaded by a corrupt and/or incompetent judge who was apparently about to renege on a formal commitment not to send the defendant to prison following the completion of a mandatory 90-day diagnostic evaluation sentence. Those who insist the director was somehow misled into believing that his plea bargain in front of Rittenband would preclude the threat of further jail time may be interested in the previously sealed transcript of the critical August 1977 hearing at which Polanski pleaded guilty to a single reduced count of unlawful sex with a minor. As part of the process, the defendant was required to answer 62 separate questions posed by the district attorney in the case, among them the following exchange:

Q: Mr. Polanski, who do you believe will decide what your ultimate sentence will be in this matter?

A: The judge.

Q: Who do you think will decide whether or not you will get probation?

A: The judge.

Q: Who do you think will determine whether the sentence will be a felony or a misdemeanor?

A: The judge.

Q: Do you understand that at this time the court has not made any decision as to what sentence you will receive?

A: Yes.

Now turning from the criminal, or depredatory, to the small matter of whether Polanski’s films are actually any good. The director’s first full-length feature Knife in the Water (1962) is a beautifully crafted, if at times noticeably budget-conscious, thriller that offers the classic Polanskian brew of claustrophobia, latent menace, voyeurism, class antagonisms and sexual tension, in this case set aboard a small yacht. Seen today, it still seems as fresh as the moment it was released more than sixty years ago. Among other charms, Knife has some of the most convincing examples of the kind of pure and honest personal hatred that can pass for conversation in a marriage since Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? All cult black and white Polish films should be shot on a shoestring, in an increasingly mutinous atmosphere among their cast and crew – that way they might be half as good as this one. Perhaps the best sign of the film’s artistic merits came when its distributors arranged a special showing for members of the Polish cabinet in Warsaw, and the state’s hardline communist party boss Wladyslaw Gomulka expressed his reservations about it by hurling an ashtray at the screen.

Following that there was a wonderfully twisted thriller named Repulsion, shot in London, which charts the mental disintegration of a young woman who lives with her sister on the top floor of a seedy South Kensington mansion block. As with Knife, the film occasionally betrays its budget-related shortcomings, but still shows an originality and a lightness of touch well beyond the stock Hammer-horror genre that its producers, a faintly comic-opera pair of East End entrepreneurs named Michael Klinger and Tony Tenser, had in mind. The gradual crack-up of what Polanski calls ‘an angelic-looking girl with a soiled halo’, bereft of any of the sort of state emotional-welfare apparatus we might expect today, is what seems most shocking to modern viewers: both pitiable and ugly.

Repulsion was perhaps the logical curtain-raiser to Polanski’s first significant, and commercially successful, venture, 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby. Essentially, it’s the tale of a young woman whose world, like that of the heroine in Repulsion, spirals into a living hell once she becomes pregnant – inseminated by Beelzebub himself, apparently – with her first child. Things soon take a downward turn. At first the neighbours in the woman’s New York apartment building show an unusual interest in her welfare, and in time weird chanting can be heard through the walls at night. Then another neighbour commits suicide by jumping out of a window. When the new mother finally gives birth, she’s at first told that her child has died on delivery. Hearing its cries from the next room, she locates her infant son, who it appears has highly unusual eyes, causing Rosemary to clap a hand over her mouth to stifle a scream. It’s all just a touch extreme, and the veteran actress Ruth Gordon, playing one of Rosemary’s neighbours, appears to have inadvertently wandered in from the set of a knockabout comedy, but set against this the direction itself is crisp, unpretentious and rarely stoops to cliché. The film brought Polanski both fame and fortune, but perhaps more importantly saddled him with the faintly unsavoury reputation he arguably still enjoys today. To some, it was as though the director himself had sold his soul to the devil, as some real-life equivalent of the Faustian pact seemingly entered into by Rosemary’s neighbours and tormentors. One widely-seen press headline of the time, parodying the advertising for Rosemary’s Baby, ran ‘Pray for Roman Polanski’.

After that came a notably sanguinary Macbeth, which most critics took as a cathartic exercise by Polanski, whose wife had been murdered the previous year, followed by Chinatown, a hard-boiled but gently paced saga of big-city corruption, peopled by Raymond Chandler-style wiseguys and featuring a memorable cameo by the director himself as a knife-wielding thug.

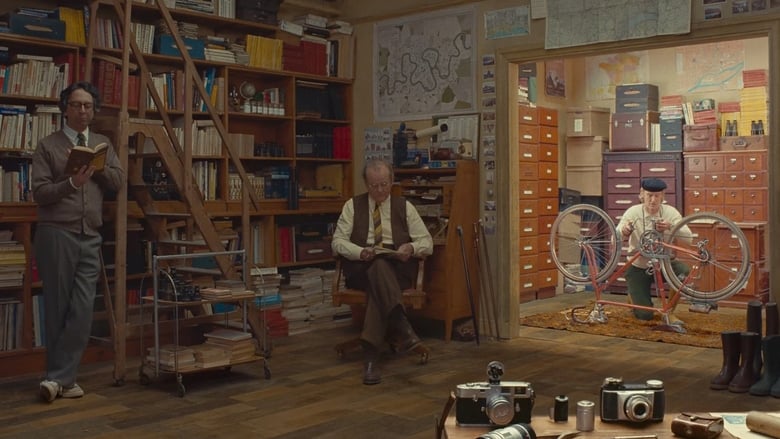

We can perhaps draw a discreet veil over the years from around 1975 to 2002, although the visually sumptuous Tess (1979) – like Macbeth, inviting numerous Freudian, if not overtly autobiographical interpretations, with its central plot of a young girl sexually violated by an older man – had both its admirers and detractors. Perhaps it’s enough to say that Polanski brought a distinct vision to bear in almost all his films, good or bad, and that this included a technical expertise (he remains an acknowledged master of matters such as camera lenses and stage-dressing) not as common in even the most prominent directors as one might think, as well as a tendency to explore the darker side of the human condition: the idea that we’re essentially adrift in a hostile world, the butt of some cosmic jest of unfathomable cruelty. ‘My characters’ destinies [are] the result of apparently meaningless coincidence,’ Polanski once said, which would appear to apply to much of his own career. One of the most pronounced themes, rarely far from the surface in his scripts, is the subject of betrayal, and, by extension, death – of compelling interest to the man whose mother, wife and unborn son were all murdered – and the inevitable survivor’s guilt. When asked about the violence in his films, muted as it may seem by modern standards, Polanski inevitably notes that he does no more than show the world around him, and whatever else he’s surely one of the few directors, living or dead, to have experienced quite as many of the twentieth century’s homicidal monsters at first hand. ‘People talk about the autobiographical aspect of Roman’s work,’ the critic and Polanski collaborator Ken Tynan once observed. ‘But his life’s much more interesting than that. The cliffhangers end with real falls.’

This somehow leads irresistibly to 2002’s The Pianist, the affecting Holocaust drama for which Polanski won his first and as yet only Academy Award. Surely one of the film’s many attractions is that it dares to underplay the obvious horror of the subject matter, never pandering to the audience with the sort of pity-of-it-all approach taken by other directors treating broadly the same material. In Polanski’s world there are no soaring choirs to mark the moments of redemption, and no Jaws-like thudding to signal the perils. The film’s climactic confrontation, when a leather-clad SS officer asks the eponymous musician Wladyslaw Szpilman to prove he can play the piano, the stark implication being that he’ll be shot if he can’t, stands as an exquisite example of the power of understatement. Where another director might have given us close-ups of squinting eyes and sweaty palms, Polanski lets the scene unfold quietly, with just the right balance of tension and release. Instead of the panoramic sweep of a Schindler’s List, The Pianist confines itself to a more modest and specific set of events. In scaling down the action to a single, not invariably heroic figure, it invites the audience members to put themselves in Szpilman’s shoes, and so achieves an impact that Spielberg’s worthy but heavy-going epic had somehow lacked. Taken as a whole, the film remains Polanski’s masterpiece, one that surprises through its understated and irresistible power to move.

It remains only to note that when Polanski won his Oscar for The Pianist, he wisely elected not to personally attend the awards ceremony in Los Angeles. Had he done so, he would presumably have been met not by the traditional Academy limousine but by an armed police detail, which would have executed the outstanding warrant for his arrest and transported him to the nearest jail. Polanski’s friend Harrison Ford collected the trophy on his behalf, and was later able to fly to Paris and present it to him in person. The Oscar ceremony itself took place on 23 March 2003. By a morbid coincidence, it was sixty years to the day since Polanski’s father Ryszard had been marched off to the Mauthausen concentration camp, thus exposing his son to the full horrors of the Nazi occupation of Poland. On at least one level, the whole ordeal now finally seemed to have been brought full circle. ‘I am deeply moved to be rewarded for The Pianist. It relates to the events so close to my own life, the events that led me to comprehend that art can transform pain,’ Polanski said in a statement from his Paris exile.

It is not a bad epitaph on his career as a whole.

CHRISTOPHER SANDFORD is a prolific writer on subjects ranging from politics to rock music. His latest book is Polanski: A Biography (Random House)