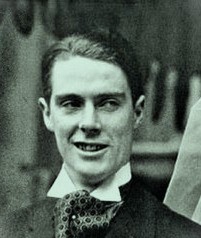

CHRISTOPHER SANDFORD honours a unique novelist

A framed letter faces me on the desk as I write this. Composed in an engaging mix of spidery longhand and erratic manual-typewriting, with a rubber-stamped phone number giving it a further touch of the haphazard, dated September 1992, it reads:

Dear Mr. Sandford

I am delighted you like Dance well enough to want more, but I have always set me [sic] face against doing any sort of coda after I finished, because even while I was writing, it was difficult enough to keep the same tone of voice, and now that I am so ancient it would be quite impossible. All the same, kind of you to ask.

Yours sincerely

Anthony Powell

PS I expect you know Hilary Spurling’s Handbook to a Dance (Heinemann), which is very good and amusing.

It was the beginning of a modest correspondence I kept up with Powell, author of the magisterial 12-novel sequence A Dance to the Music of Time – the last volume of which appeared a blink-of-an-eye half-century ago, in September 1975 – during the remaining eight years of his life. He would have been 86 at the time of our initial exchange, and by all accounts was becoming increasingly crotchety, not least in the matter of the correct pronunciation of a name he insisted should rhyme with ‘bowl’, not ‘trowel’.

One freezing January morning later in the 1990s, a plumber answered an urgent call to attend to a burst pipe at a large Georgian house in the English countryside near Bath. An elderly man dressed in tweed answered the door.

“Mr. Powell?” asked the plumber, pronouncing it Pow-ell.

“There is no one here of that name,” replied the old man.

“Oh, sorry,” said the plumber. “I must be at the wrong house.”

“I can’t help you,” said the old man.

The plumber then drove around the frozen neighbourhood before being told that Anthony Powell did indeed live in the house he had just visited. So he returned.

The same man opened the door. This time the plumber enquired, “Does a Mr. Powell live here?” “No,” the elderly gentleman said. “However, do you mean Pole?” The plumber nodded. “Ah! Then go round to the back door, the leak is in the kitchen.”

This is surely a scene that could have been torn direct from the pages of Dance, peopled as it is by a cast of louche London artistic types, colourful military coves and eccentric English landed squires. The sequence has been described as everything from “Proust anglicised” to “a kind of social accountancy, and not much more enlivening than the financial sort.” Evelyn Waugh’s son Auberon (of whom more presently) thought the whole thing no more than “an early upmarket TV soap.” PG Wodehouse, by contrast, was “absolutely stunned by [Powell’s] artistry.” Fifty years later, the critical divide persists. Powell’s magnum opus has become an odd sort of cult work, its reputation kept alive not just by the devotees who have loved or still love it – among them Christopher Hitchens, Stephen King and Clive James, who called Dance “the best modern novel since Ulysses” – but by those who love to hate it and consider the whole thing a testament to staleness.

I’m in the supporters’ camp. Taken as a whole, the Dance’s twelve-book sequence strikes me as an unsurpassable panorama of a vanished Britain, and – lest you not yet have made its acquaintance – an almost chemically addictive joy to read; hence my brazen request of its author for more of the same. But here’s a curious thing. As I say, I had the pleasure of corresponding with and meeting Powell himself, and have read and re-read both his novels and the various biographies, particularly the aforesaid Hilary Spurling’s, and yet the more one comes to learn about the man the more elusive he seems to be as a flesh-and-blood human being – not to mention one whose life took him from a lonely and nomadic boyhood at around the time of the First World War to the twilight years spent as an obsessive genealogist and high-and-dry Tory who, almost incredibly, survived long enough to see in the twenty-first century. All I can add by way of a physical sketch is that in person Powell was compact, immaculately turned out in a manner that seemed to have been frozen in place since about the year 1933, with a piercing stare under incongruously untidy eyebrows, and a sharp, nasal voice that was close to a comic turn in itself.

On the other hand, in a canonical work full of shadows, as Powell nearly wrote in Books Do Furnish a Room, certain characters are bound to be shadowy. There is the superbly detached role, to cite only the most obvious example, he gives his alter ego Nick Jenkins, the narrator of A Dance to the Music of Time. Both the author and his fictional self seem to have gone through life as scrupulously neutral observers of the human condition, rarely if ever offering a declarative judgement on people or events, let alone asserting their own identities. There’s a section in the early wartime novel The Valley of Bones, about midway through the whole sequence, where Jenkins’s wife Isobel suddenly goes into labour with the couple’s first child, an event she announces with the line: ‘Look here, I’m sorry to have to call attention to myself at this moment, but I’m feeling awfully funny. I think perhaps I’d better go to my room.’ This same sense of supreme self-effacement applied equally to the author who gave her the lines to speak, who himself once said, ‘I have absolutely no clear picture of myself’, and confessed that he began writing shortly after coming down from Oxford in large part because he couldn’t think of anything else to do, rather than due to any particular aptitude or talent.

With respect to that judgement, it strikes me as taking diffidence to unnatural lengths, if not to qualify Powell as a martyr to false modesty. Taken as a whole, Dance is a fiendishly intricate literary feat, which its author carries off throughout the whole 3,000-page, million-word sequence as it passes over some sixty years of English social history, conveyed through perfectly ordinary (which is to say, often absurd) situations rather than conventional drama. It remains a singular, and brilliantly sustained, achievement of twentieth-century letters. Powell himself, as conveyed by his biographers, may be retiring to the point of near invisibility, but his great roman fleuve more than once touches the artistic heights occupied by P G Wodehouse and Evelyn Waugh.

Yes, to address a frequently heard opinion of the Dance sequence, there are moments where the prose is arid and the terminology fustily dated. Powell’s characters adopt “sun spectacles”, for example, when finding themselves in “not wholly inclement climes”, or travel on that “uncomfortable but commodious conveyance” the Clapham omnibus. It might be said that the author sometimes makes heavy work of simply getting the reader from A to B. When introducing the minor character Rosie Manasch, a patron of the arts who emerges in the tenth installment of the series, Books Do Furnish a Room, Powell notes: “In the course of further preliminary conclaves with Bagshaw on the subject of Fission’s first number, mention was again made of an additional personage, a woman, who was backing the magazine.”

Or, of a pair of MPs, Labour and Conservative, meeting at a funeral described in the same book: “The two had gravitated together in response to that immutable law of nature which rules that the whole confraternity of politicians prefers to operate within the closed circle of its own initiates, rather than waste time with outsiders; differences of party and opinion having little or no bearing upon the preference.”

The Dance, then, may have an old-fashioned roll to it, but beyond the occasional dowager style Powell’s genius was surely to sustain a vibrant, and highly credible, self-contained imaginative world. Some of the series’ individual performers recur from book to book, going on from school to university, their careers interweaving, marrying, divorcing, fighting for their country, haunting the rackety dives of postwar Soho, and finally catching up with life in the hedonistic, culturally vapid 1970s. As anyone who’s ever written a novel will tell you, it’s hard enough to plausibly develop even a single life over any protracted amount of time. Powell does this for literally scores of deftly sketched, sometimes honourable, not infrequently comic, invariably compelling leading characters, appearing and disappearing and then reappearing at intervals, all in perfectly logical order, guiding us from the Great War to the moon landings in the process, with the subordinate cast, typically drawn from the English literary or artistic demi-monde, providing the crucial ballast.

In short, Powell’s achievement is that of the architect as well as the author. The delicate slapstick of events is slowly drawn together, the apparent coincidences and chance reunions never less than true to life, the touch exquisitely light in its sardonic treatment of the material. Here is Powell’s doppelgänger Nick Jenkins, musing in a rare moment of intellectual candour, in the third book of the sequence The Acceptance World:

I began to brood on the complexity of writing a novel about English life, a subject difficult enough to handle with authenticity even of a crudely naturalistic sort, even more to convey the inner truth of the things observed … Intricacies of social life make English habits unyielding to simplification, while understatement and irony – in which all classes of this island converse – upset the normal emphasis of reported speech.

As often noted, Powell’s opus is really a form of elegant soap opera, with cyclical themes and characters, and an infallible knack – the envy of many a television screenwriter – of ending each episode with a crisis. (Powell spent the winter of 1936-37 script-doctoring in Hollywood for Warner Brothers, an experience, however venal, he later admitted was invaluable ‘when one came to the engineering’ of Dance.) When the series’ narrator joins the army in 1939, he is promptly assigned to the corrosive Kenneth Widmerpool, his school contemporary of twenty years earlier. The physically clumsy, socially tone-deaf Widmerpool then returns at intervals in each of the remaining novels of the series, variously translated from soldier to businessman to MP to university chancellor-cum-pagan cultist, a figure at once ludicrous and sinister, and taken as a whole one of the great comic ogres of 20th century literature. It says something for Powell’s artistry that there was intense competition among his circle to be publicly identified as the model for a character synonymous with the harsh and manipulative use of power, the author’s brother-in-law Lord Longford laying the strongest claim, but the likes of Powell’s wartime chief Denis Capel-Dunn, the richly-tinted jurist and latterly Lord Chancellor, Reginald Manningham-Buller, the art historian Gerald Reitlinger, and even the sometime Tory prime minister Ted Heath all making a persuasive bid for consideration.

If not exactly required reading these days, Powell’s masterpiece remains one of Western literature’s enduring feats, and might even be one of the few things that nurtures an awareness of an older, more reticent England, not dead, perhaps, but gone into hiding until the present tabloid version self-destructs. The author himself lived long enough to see such bracing developments in British life as the advent of punk rock and of Sarah, Duchess of York, as well as a modern idiom in which domestics would come to refer to assaults, not servants – all recorded in his wonderfully mordant late-life diaries. A modest man with a profound dislike of reckless informality and self-promotion, Powell continued working almost until the end, publishing the final volume of his Journals in 1997, not long before Channel 4 finally succeeded in bringing a seven-hour version of his magnum opus to television screens. He once told me in characteristic tones that he was “not wholly unsatisfied” by the Dance sequence (in written, if not screen format) as a whole. It remains good literary fun, like all the best fiction a brilliantly contrived escape from the banality of the real world. The author Michael Frayn perhaps put it best when he recalled of stumbling on Powell for the first time: “It was like discovering a complete civilisation – and not in some remote valley of the Andes or the Himalayas, but in the midst of my own life … Another world had been superimposed upon my own, refracting and reflecting it.”

As mentioned, Powell brought his opus to a triumphant conclusion with its final installment, Hearing Secret Harmonies, as long ago as September 1975, and resisted all overtures to revive it from behind its marble slab at any point during the remaining quarter-century of his life. That decision notwithstanding, the years in question were far from without interest for him. Apart from turning out a stream of increasingly free-form reviews and memoirs, Powell found himself at the age of 84 embroiled in one of those explosive literary feuds the English seem to do almost as well as their genius for the political sex scandal, and which itself might have graced the pages of Dance. His adversary in the matter was Evelyn Waugh’s eldest son, Auberon, who published a damning review of Powell’s latest volume of memoirs in the Sunday Telegraph, a paper to which they were both long-time contributors. When the moment came, Hilary Spurling would pass lightly over the incident in her official life of her subject by taking what could be called the psychological approach to the whole affair. Waugh Jr, she writes, had himself not long beforehand published a memoir,

…contain[ing] a scary portrait of Evelyn as a monstrous egoist who regarded all his sons, and this one in particular, as rivals to be snubbed, derided and put down. Even in his own distress, Powell regarded young Auberon’s response [to his book] as essentially vicarious, the vengeful product of a largely loveless childhood.

Be that as it may, Powell went ballistic, severing his relations with the Telegraph, who rather bizarrely commissioned a bust of their departing eminence grise but then found they had nowhere to put it. It perched for a while on an office filing cabinet. The Powells and the Waughs never spoke again. Somehow, the whole episode could once again have been taken from one of those darkly comic contemplations of the postwar London literary scene that enliven Books Do Furnish a Room, the tenth and in my judgement best individual installment of the Dance.

Anthony Powell was that highly overused word, unique. The room he occupied in the mansion of English literature was distinct, located on a level where no one else regularly ascended, although Evelyn Waugh might be said to have inhabited broadly the same space. Any reader not yet familiar with the Dance, widely available today in various formats, should treat themselves to one or more of its volumes immediately. The dozen subsidiary novels, so beautifully written, so riotously entertaining, for all their pervasive air of English melancholy and social decay, are the work of a master of his craft. We have not his equal.

CHRISTOPHER SANDFORD’s book The Cricketers of 1945: Rising From the Ashes of the Second World War (Pitch Publishing) is available now.