R. J. STOVE says reports of the death of Australian classical music education have been greatly exaggerated

The most satisfying paid regular employment that I have ever experienced concluded on 11 November 2021. For a twelve-week course, I worked as a sessional tutor under the University of Sydney’s auspices. The tutorials – overarching title: ‘Music in Western Culture’ – catered not purely for first-year music majors, but for first-year majors in other fields too. (As I write this paragraph, there remains some essay-marking for me to complete.)

Initially, I felt overwhelming panic, thanks to the requirement for near-Lisztian virtuosity in the Zoom-PowerPoint combination. ‘Have I turned the sound on?’ ‘Have I turned it off?’ ‘Have I accidentally shared the answers to tutorial questions?’ Of the course’s first two weeks, almost no memories remain except my visceral technophobia.

Besides, what (I wondered) if my students turned out to be a monstrous regiment of snowflakes, merrily toppling the nearest Queen Victoria monument, when not ululating into their smartphones about being ‘triggered’ by my own ‘Eurocentric’, ‘cisgendered,’ ‘heteronormative’ ‘microaggressions’ and ‘cultural appropriations’ upholding ‘the patriarchy’? Could my restricted didactic aptitude ensure those ‘safe spaces’ that Homo Snowflakiens considers indispensable?

My fears proved excessive. Zoom’s malfunctions and eastern Australia’s draconian lockdowns notwithstanding, I received from students consistent politeness. Whether this resulted from good luck – or from, instead, some antecedent administrative colander by which the palpably woke had been strained out, before they could contaminate the main dish – others must determine. Possibly a third cause prevailed.

All in all, my first salaried academic occupation gave me intense pleasure. The moment when everything clicked occurred as I replayed one of the tutorials’ set pieces: a Haydn piano sonata scintillatingly performed by L’viv-born, Manhattan-based Emanuel Ax. Suddenly I realised: ‘I’m receiving federal subsidies for listening to this marvellous stuff.’

Last summer’s dirge from a prominent British musicologist, who has huffily left the discipline (short version: ‘Goodbye, cruel world’), inspires not the faintest empathetic echo in my bosom. The musicologist achieved a full professorship before he had turned thirty-eight; maybe therein lies his whole trouble.

Yes, my job had its nuisances, principally an exasperating holdup in my wages’ arrival, plus a nasty bout of mid-term illness which required my hospitalisation (and which complicated my already overworked colleagues’ timetables). About these nuisances I shall say little, partly because I crave further university employment, but chiefly because such irritants come with fallen human nature. Erstwhile Esquire boss Arnold Gingrich cherished a magnificently orotund sentence redeeming, circa 1947, one otherwise humdrum epistle to the editor: ‘I find no fault in Esquire that I do not find with the age that produced it.’ Mutatis mutandis, this encapsulates my response to Australian academe.

+++

What straightaway impressed me, regarding the ‘Music in Western Culture’ course, was its predominating old-fashioned decorum. The main textbook, A History of Western Music, is but a revision – by Indiana University’s J. Peter Burkholder – of an identically named volume known earlier as ‘Palisca’ and even earlier as ‘Grout’ (after the previous versions’ respective authors: C.V. Palisca and Donald J. Grout, who died in, respectively, 2001 and 1987).

We who grew up with ‘Palisca’ and ‘Grout’ found much of Burkholder’s tome familiar. True, Burkholder cites hip-hop and sexual identity politics, as Grout would never have done; true, feminist considerations now compel coverage of female composers – Hildegard of Bingen among them – whom Palisca and Grout either underrated or omitted. These are incidentals. Aesthetic detachment marks all three musicologists: their audiences, happily, will find no clues as to which genres are the authors’ own favourites.

It scarcely requires accentuating how objectionable this dignified scholastic model is within Critical Race Theory’s snake-pit, which one Philip Ewell now inhabits. Ewell (of City University New York) bears the same relation to a conventional apparatchik like Norman Lebrecht that Wilhelm Reich bore to Freud, Foucault to Sartre, and Pol Pot to Brezhnev.

The Wuhan market, as it were, which first disseminated Ewell’s ‘thinking’ was a 2019 lecture to the blandly named Society for Music Theory, where Ewell demanded that Western music’s ‘white racial frame’ be ‘decolonised.’ (He nowhere condescended to explain who would do the decolonising. R. Kelly?) Ewell cast special opprobrium upon theorist Heinrich Schenker, a Jewish thinker never previously charged with white supremacism. Ordinary teaching of Western staff notation, teaching liable to necessitate such elitist hierarchical signifiers as ‘dominant’ and ‘subdominant,’ goaded Ewell to rage.

Timothy Jackson, a white liberal at the University of North Texas, organised a firm but courteous refutation of Ewell. This refutation – involving fifteen writers – occupied an issue of the magazine that Jackson co-edits, the Journal of Schenkerian Studies. The issue’s appearance activated frenzied calls for Jackson’s dismissal. At his references to racial slurs among Ewell’s beloved rappers, the anti-Jackson brigade took particular offence. One touch of (inadvertent) farce emerged from Ewell’s champions, when a female Canadian pundit treated the world to its least felicitous recent neologism: she derided Schenker’s white female adherents as ‘SchenKarens.’

Throughout my own work contract, I heard not a syllable of Ewell-advocacy. This argues for some inherent common sense within the Australian university system.

+++

The system had other merits. On average, each of my online tutorials contained twelve students. This was (apologies for sounding Panglossian) the best of all possible class sizes. Too small a group, and a single garrulous individual can monopolise the whole hour. Too large a group encourages dumbed-down populism. The latter hazard could well plague all vast programmes aiming to save the world through one colossal music lesson.

Of the Orff and Kodály instructional methods’ details, I lack the competence to speak. Alas, no such mitigating circumstances characterise the Suzuki method, which its founder’s fake doctorate and bogus claims to Weimar Republic tuition make hard to stomach now. Nor do they characterise the Venezuela-derived El Sistema. Once viewed as the ultimate in pedagogical chic, El Sistema prompted in 2014 a devastating book-length exposé by Geoff Baker, left-wing musicologist and Guardian correspondent. Baker’s harrowing disclosures incorporate accounts of El Sistema’s explicitly erotic corruption.

So much for the New York Times feature on El Sistema (16 February 2012) with a banner typifying the method’s longstanding media hype about proletarian empowerment: ‘Fighting Poverty, Armed With Violins.’ The perfect modern validation, surely, of William Dean Howells’s acerbic epigram ‘Americans want tragedies with happy endings.’

+++

Naturally ‘Music in Western Culture’ was spared all carnal predators and all holders of counterfeit PhDs. My largely congenial experiences engendered my quiet, healthy scepticism towards anti-intellectual harangues from Fox News’s talking heads. Had I believed apocalyptic rhetoricians so obsessive that they could probably detect woke outrages on the planet Saturn, I would have been too scared to do my job.

Unlike those talking heads, I acutely recollect Australia’s higher education during the Cold War. This had its joys, above all Sydney’s Dr Andrew Riemer – specialist in Elizabethan-Jacobean drama – who gave the clearest, most fair-minded lectures which I have heard on any topic. (He subsequently produced memoirs as readable as, and striking deeper than, Clive James’s.)

Yet no milieu is less apt than my undergraduate youth to provoke my predispositions, themselves infinitesimally sparse, towards Golden Age nostalgia. Is woke craziness in 2021 truly more malevolent in its effects on academe than was Martin Bernal’s craziness (the briefly modish ‘Black Athena’ phantasm) in 1991? Or Sandinista craziness in 1981? Or anti-Vietnam-War craziness in 1971? Or D.H. Lawrence’s craziness in 1961? Or – lest we forget – Freudian craziness in 1951? Frankly, I doubt it. (I speak as one who, when a small and always fearful child, repeatedly wondered whether my father would get home alive after his daily encounters with draft-dodging, vandalising mobs who shrieked ‘Ho, Ho, Ho Chi Minh! / The NLF is gonna win!’.)

Against several benchmarks, Australian humanities departments have improved. A trivial but significant amelioration: I marvel at how attractive their latter-day recordings of medieval music are.

Students no longer gain their formative exposures to the Middle Ages’ sounds, as I gained lots of mine forty-one years ago, through the Historical Anthology of Music series (surface-noise-infested American LPs supplementing a primer that dated from 1946). There, every second track seemed to comprise bleating from three Teutonic nonagenarians with vibratos almost wide enough to march a platoon through. It was, furthermore, mandatory to capture the nonagenarians in an acoustic resembling someone’s broom-cupboard. Today, anyone trawling through music schools’ libraries (to say nothing of Spotify or YouTube) can find more abundant and beauteous early-music renditions inside an hour than we in 1980 could have located inside six months.

+++

More momentous are universities’ newish regulations for conduct. I think of those Australian academics in the 1980s – wielding influence disproportionate to their limited numbers – who at best channelled Lucky Jim Dixon, and at worst channelled Walter Mitty. Thanks in part to online packages like Turnitin, sanctions against plagiarism (whoever commits it) have teeth now, whereas in the 1980s no such sanctions existed. Admirers of that classic 1948 film The Red Shoes will appreciate the impunity with which unscrupulous teachers once thieved pupils’ material, in music as elsewhere.

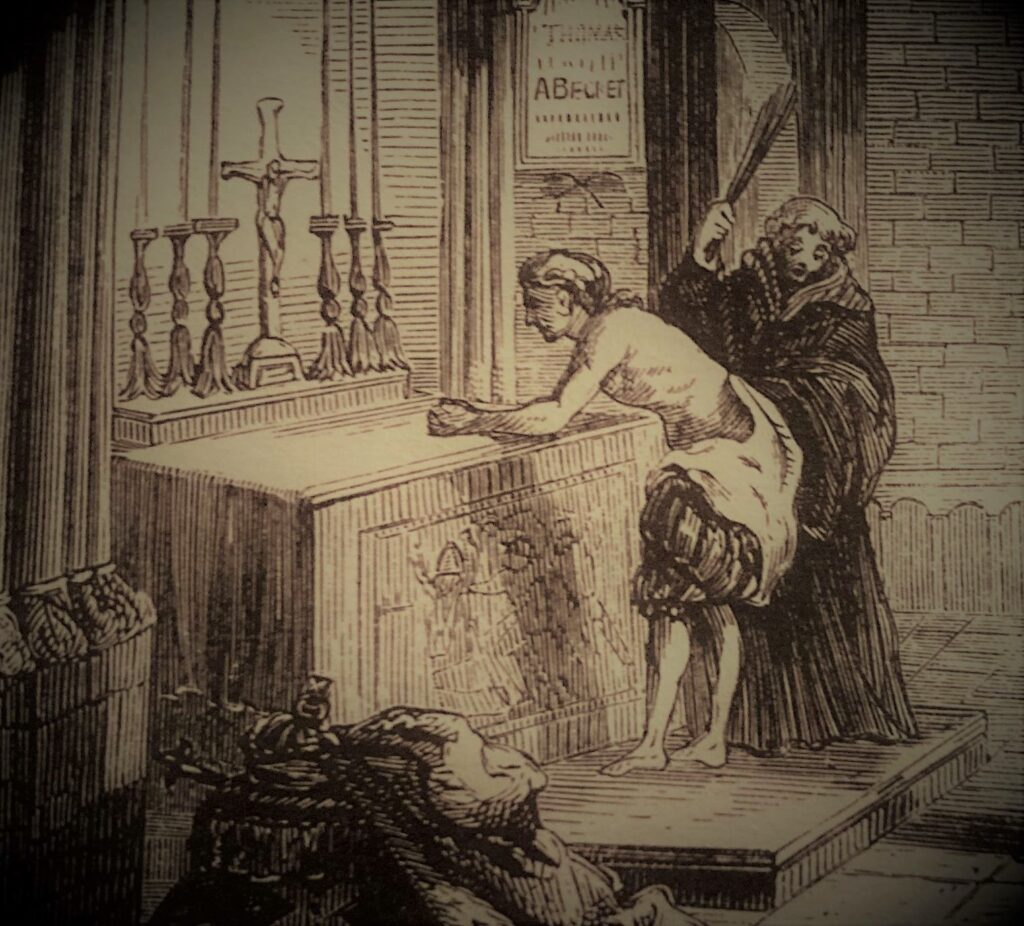

Heaven knows, present-day Australian students are susceptible enough to the pernicious worldviews expounded by Peter Singer. That said, I – unlike those students – am conversant with the equally pernicious worldviews expounded by the University of Sydney’s 1927–1958 philosophy professor John Anderson: militantly anti-Christian demagogue and long-time Communist Party fellow-traveller, with compulsive unwillingness to differentiate the ontological concept of ‘female undergraduate’ from that of ‘sex toy.’ Nor was Anderson’s unwillingness unique. While the worst predation flourished amid the Age of Aquarius, as late as 1984 our juvenile gossip included a pervasive wisecrack concerning the relevant transaction: ‘a lay for an A.’ And this taxpayer-funded bonking was, be it emphasised, entirely legal.

Some outstandingly toxic teacher-student relationships encompassed no physical acts. Wherever degrees are both rare and esteemed, opportunities for students to levy emotional blackmail against teachers (or vice versa) proliferate. Joyce Carol Oates’s short story ‘In the Region of Ice’ frighteningly depicts the inexorable persecution of a teaching nun by her male protégé.

‘Well, for good or evil’ – I here quote Chesterton’s Autobiography – ‘that is all dead.’ Manipulative teacher-student interactions will seldom eventuate when each participant is a mere flickering Zoom image to the other. Moreover, with the nation’s 1989–1992 university reforms, the droit du seigneur over female students (not to mention over female secretaries) disappeared from Australian tenured life’s fringe-benefits.

This tenured life itself – like its British counterpart – has dwindled to a rarity which in the USA is unimaginable. In 2006, one Australian lecturer told Inez Baranay, a Sydney-based novelist-essayist: ‘the area I teach in has not appointed any tenured academics in ten years.’ Undoubtedly, entrenching casual labour carries risks; in Sydney’s and Melbourne’s higher education systems, wage theft has reached alarming levels. But likewise undoubtedly, the pre-1989 antipodean routine of near-automatic tenure mollycoddled so many layabouts that it just had to be scrapped.

Australia’s sustained Cold War prosperity facilitated tenure’s abuse. The abolition of student fees in 1974, by Gough Whitlam’s government, merely reinforced the long-extant system whereby eighty per cent of local undergraduates avoided paying fees anyhow (the University of Western Australia, in Perth, charged no fees at all). Nor, in that profligate epoch, did stringent selection criteria for staffers invariably operate. Thank goodness, arbiters of Australian students’ destinies no longer include that frequent pest from my young manhood: the rancorous idler who had not published a solitary article or, indeed, drawn a solitary sober breath since around 1960.

+++

Another, and unexpected, modern improvement concerns religion. Current Australian academe has got ninety-nine problems, but Freemasonry ain’t one. (Read the 1997 biography of Australia’s classics scholar F.J.H. Letters, by his widow Kathleen, if you dispute local lodges’ former influence over universities.) Whatever my attire’s shortcomings, no-one has commanded me to rectify these by procuring a leather apron.

Neither have any university personnel weaponised against me my Catholicism, shared with Letters himself, and discoverable through five minutes on Google. To Australians my age or older, such newfound tolerance of ‘papists’ is mind-boggling. We recall the longevity of a tabloid, The Rock, which for half a century after 1944 spewed Klan-style vilification against Catholicism (it greeted sponsored Italian immigrants with headlines like ‘450 Human Wogs Arrive’).

Hardly anyone admitted to reading The Rock, but that fact indicates how many liars Australia had. Because at the tabloid’s pre-Vatican-II apex, it sold 30,000 copies per issue: a remarkable total in a country with under eleven million inhabitants, and quite adequate for coercing numerous politicians into servility. Witnessing The Rock’s diatribes and their parliamentary counterparts, Scottish newspaperman John Douglas Pringle – an unbeliever – lamented: ‘Anti-Catholic feeling is extremely strong in Australia. From time to time it bursts out like lava from a sleeping volcano, burning and destroying everything it touches.’

Of course, as the mendacious campaigns against Cardinal Pell showed, this emotion has not vanished from Australia’s midst. It still governs our state police forces and schoolteachers’ unions; all of our gutter media (what are our surviving non-gutter media, pray tell?); much of our medical establishment; and much of our judiciary. Nonetheless, for whatever reason, anti-Catholic wrath now leaves New South Wales’s universities undisturbed. Without this welcome change, I could never have attained academic emolument.

Decades back, my late Sydney chaplain friend Father Paul Stenhouse once parked his car on campus, having left visible his dashboard’s Virgin Mary statuette; he returned to find the windshield smashed. These days, comparable sectarian malevolence incurs serious penalties, Twitter castigation included. Back then, had Father Stenhouse formally submitted a complaint, campus officials would have all but laughed in his face.

Cardinal Sir Norman Gilroy, Sydney’s Catholic archbishop from 1940 to 1971, had discouraged his flock from university attendance in general. What with Marian figurines being punishable by smashed windshields – and what with Anderson the bellicose Christophobe on the prowl, sizing up the female talent – the Cardinal was conceivably on to something.

+++

Altogether, therefore, I remain as conscious of Australian universities’ past defects as of their present ones. Whilst the latter are undeniable, I question the novelty and the immediate nature of their threat.

Incontrovertibly, it is dreadful that various full-fee-paying foreign students now graduate despite their limited spoken and written English. But even that vexation, albeit new in degree, has a prototype in kind: the Colombo Plan’s late-1950s zenith. This zenith placed academics like my father in loco parentis to numerous young Southeast Asians, who too often secured Australian degrees while insufficiently Anglophone to request a train-ticket unassisted, let alone to grasp my father’s lectures on David Hume’s metaphysics. In Dad’s own weary but eloquent aphorism: ‘the challenge is to fail.’

As for the reckless dream of higher education for all, surely the pandemic dispelled that dream faster than any libertarian think-tank could do. COVID has intensified our established dependence on couriers, cleaners, nurses, postal clerks, supermarket clerks, warehouse workers, slaughterhouse workers, aged-care workers, truck-drivers, and garbage-collectors, all of whom can acquire their specific proficiencies with not the slightest collegiate force-feeding. No First World polis can cope without these persons for twenty-four hours. Any First World polis can cope evermore without my musicological and organ-playing functions, though my school crossing function has retained since 2016 (in coronavirus-afflicted Melbourne at that) its utilitarian efficacy.

I wish to declare only this: however Augean academe’s stables might be elsewhere, my colleagues and I kept our own minuscule domain really rather neat. Hereabouts, to update Mark Twain, the death of music teaching has been greatly exaggerated. For outsiders, combating this exaggeration will rarely matter much. But if televisual pundits grew rich from proclaiming that you yourself were dead, publicising the truth would urgently matter to you and your loved ones.

Sadly, perhaps my age (I am 59) will preclude further academic employment. Yet if offered it, would I accept it? Verily I say unto you, ‘Bring it on.’

R. J. STOVE’s organ recordings are available via the website www.arsorgani.com, and via the main streaming services (Spotify, Deezer, Apple, Tidal, YouTube).