Modern Worlds: Austrian and German Art, 1890-1940

Renée Price (ed.), Prestel/Neue Galerie, 2021, 656pp, $75/£55

ALEXANDER ADAMS is transported to a thrilling time of artistic experimentation

The Neue Galerie in New York holds one of the world’s greatest collections of German and Austrian Modernist fine and applied art. It was founded by Ronald S. Lauder and conceived of in consultation with his friend Serge Sabarsky, who owned a fine selection of the best of Austrian Expressionism, particularly by Egon Schiele. Sabarsky died in 1996, before the museum opened. When the museum opened in 2001, the intention of Lauder and team of directors and curators was to correct the bias towards French art in the historical surveys of the development of Modernism in the visual arts. Modern Worlds: Austrian and German Art, 1890-1940 is the grand catalogue of an exhibition held to celebrate the first two decades of the gallery. This review is from that catalogue.

Neue Galerie was warmly received when it opened and became highly regarded for its scholarship and the quality of its holdings. The great success of the Neue Galerie, which I have visited several times and consider an essential stop on any tour of New York museums, has made German-Austrian Modernist art now a much better understood part of art history. Among specialists, there was always an appreciation of Expressionism and Secession art, but the condensed selection of masterpieces by the very best artists, housed in a handsome beaux-arts townhouse at 1048 Fifth Avenue (built in 1914) has provided an integrated story of Modernism in Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Modern Worlds has essays on various topics relating the fine art and applied art in the collection. One by Olaf Peters discusses Max Nordau’s book Degeneration (1892), which became (posthumously) his most influential book. We should not see those opposed to degeneracy solely as representatives of traditionalism. Many critics of decadence were liberals, who took a progressive view of society. As a social Darwinist, Nordau saw degeneracy as an aspect of evolution, which would lead to the atrophying and extinction of those urban populations which succumbed to its lure, driven by circumstance and genetics towards behaviour that would not sustain reproduction of healthy individuals. He cited art as a symptom of the degeneration of culture and genetic stock.

Nordau imagined a dramatic result as the consequence of this evolutionary process for art. In his view, art would cease to exist, since those who support it would have to make room for an increasingly rational humanity for whom art would no longer be a relevant form of expression. For Nordau, art would become an atavism, and only women and children – the more intensely emotional members of the population – would still pursue it. He favoured science over art, which he judged to be an irrational symptom of psychological illness. It had to yield to the advancing process of rationalisation.[i]

Another essay by Peters discusses the splintering of arts organisations in Germany and Austria in the Jugendstil/Secession period, as artists sought to gain more control over the selection, exhibition, publication and sale of their art works. A proliferation of artists groups ran alongside the desire to distance the avant-garde from state- and royalty-sanctioned bodies, academies and established professional organisations. Opposing approaches to ornamentation within Modernism are exemplified by architect Adolf Loos (anti-ornamentation) and Gustav Klimt (pro-ornamentation). This shows that there were very different aesthetic criteria supported by members of the avant-garde, just as we find contrary strands within reactionary and traditionalist camps. The influence of collector Karl Ernst Osthaus is appraised (his collection of Expressionist art is housed at a dedicated museum in Hagen, Westphalia).

The various displays and fairs including applied art, decorative art and diorama/installations accelerated the acceptance of Modernism into daily life, as well as high culture. The influence of the Arts & Crafts movement paved the way for patrons and creators. Wiener Werkstätte was founded in 1903 and flourished as a company that produced high-quality, expensive furnishings, clothing and housewares until 1914. The advent of war severely impaired WW’s output. Limited by material and manpower shortages, and the unwillingness of the affluent to invest in luxuries during a period of upheaval, business slowed dramatically. It was revived in the inter-war period but never regained its pre-eminence, closing in 1932. WW is remembered now often in terms of the contribution of female creators and for the influence of female customers, who generally made decisions regarding the decoration of family homes. Interestingly, no less than Adolf Loos gave a lecture called “Das Wiener Weh: Die Wiener Werkstätte” (“The Viennese Woe: Wiener Werkstätte”) in 1927, condemning the decline of WW. The turn to super-luxury goods was attributed to the women who dominated the management and product design of WW in the post-1914 era.

The excellent collection of WW in the museum’s collection – surely the best collection outside Vienna – includes works by leading lights of the company. The extensiveness of the Vienna design scene is amply represented by a series of striking designs of silverware, glassware, furniture, clocks, jewellery and ceramics by Dagobert Peche, Josef Hoffmann, Koloman Moser, (Belgian) Henry van de Velde and others. The designs range from the refreshingly simple and starkly unornamented to the ostentatiously impractical. Hoffmann’s cutlery services go beyond function into objets d’art. Geometrical patterns, plain checks, straight lines and elongated or square proportions are constants. Lines that echo Art Nouveau are found mainly in early, pre-war pieces. There is a silver coffer given by Klimt to the young Alma Schindler (later Mahler), when he was courting the young beauty in 1902. Another gift from Klimt is a necklace given to Emilie Flöge the following year. Both were made by Moser. Vintage photographs of other pieces in the collection show the furniture in trade shows or the homes of the original owners.

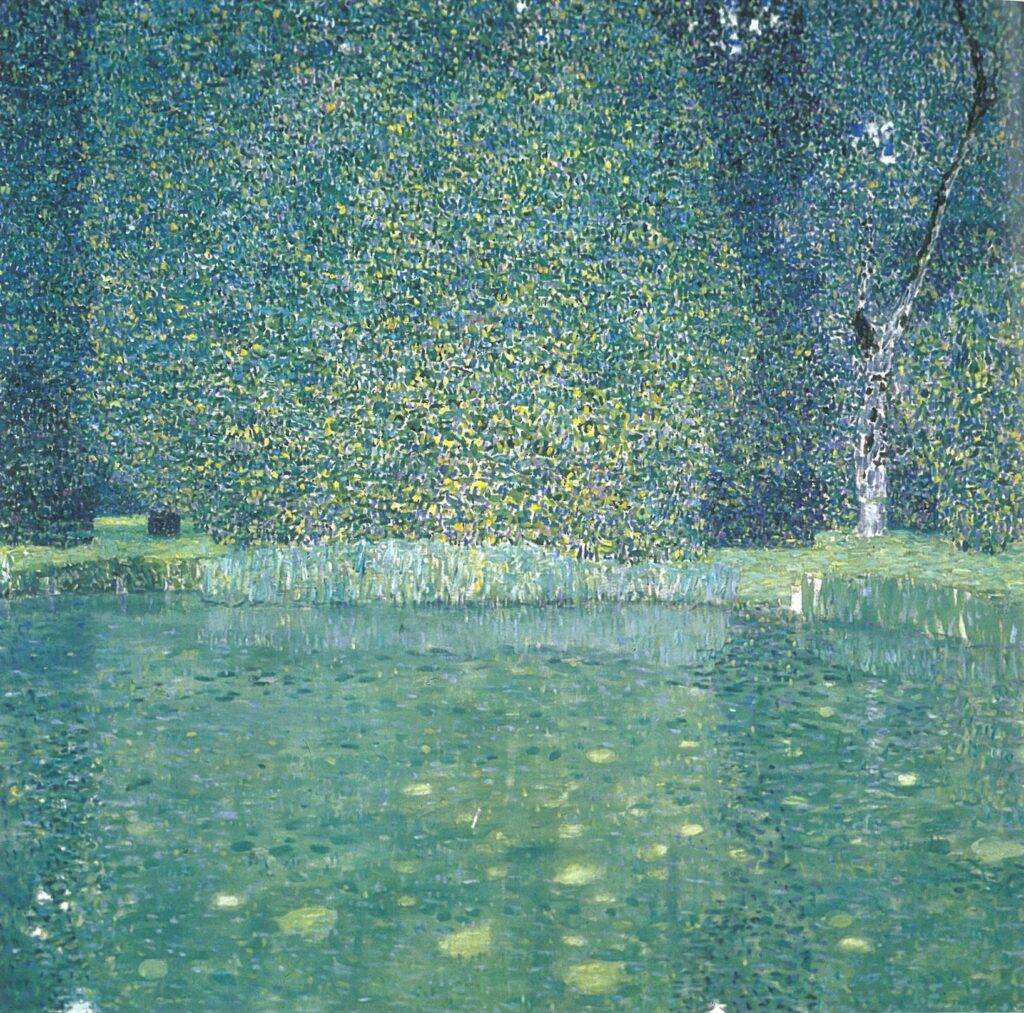

One photograph shows the star of the museum’s collection, Klimt’s gilded Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer I (1907). The painting was displayed at an exhibition of art and crafts in Mannheim in 1907, and appears to show the painting before the artist made minor modifications to it. The painting is once again displayed flanked by stone statues of kneeling youths made by George Minne, as it was in that Mannheim display. (There is a useful essay on Minne and the Germanic sculptors as precursors to the individualism of Schiele and Kokoschka’s art.) The Neue Galerie has a fine collection of Klimt drawings from all periods of the artist’s output. The square landscapes of Klimt are revolutionary. Not only is the square format (developed by Klimt in the 1890s) anti-traditional, Klimt’s flatness and decorative treatment of foliage was a radical departure from convention. Park at Kammer Castle (1909) is a typical late landscape, disorienting through the presentation of dappled surfaces that only minimally model trees, grass and water; sky is reduced to a few patches at the edges of the picture.

and was made available through the generosity of Estée Lauder

The rise of Expressionism is understandable as a reaction against the emphasis on style over substance present in the Secession. The preoccupation with distinctive visual branding – something that reached a high pitch with the opening of WW – and the targeting of the super-affluent by artists (who supposedly disdained the status-conscious administrators and participants of established salons and academies) became anathema to ambitious young artists. The prevarication of the Secession between serving the wealthy and wanting to change the lives of everyday people left little space for the emergence of the exceptional individual – the much-discussed Übermensch of Nietzsche – and the man of heroic will. What was the role of the genius under Secession? Neither designing clothing for rich heiresses nor chairs for factory refectories seemed the calling of the true artist. The development of Art Nouveau in Germany and Austria was just one manifestation with a relentless drive towards Modernist ways of living.

This development was flanked by the Lebensreform (life reform) movement, which along with the housing colony and garden city movement, the land reform movement, vegetarianism, the naturopathy movement, and the Freikörperkultur (free body culture) or nudist movement, was aimed less at the sphere of aesthetics than at everyday lifestyle. Taken together, they formulated a fundamental critique of the scarcely controllable consequences of the rapid industrialization of the German Empire in the last three decades of the nineteenth century.[ii]

In the face of the deracinating effect of modern urban life – identified by nascent social science and criminology – and the increasing artificiality and superficiality of Secession, young artists who formed the Expressionists sought authenticity and rawness. They were inspired by Edvard Munch, whose 1892 exhibition in Berlin was closed as an affront to the professionalism of the artists’ organisation that staged the exhibition. The artists association Brücke (“bridge”) was founded on 7 June 1905 in Dresden, comprising Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel, Karl Schmidt-Rottluff and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner. It later included Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein and Otto Mueller. The artists (some of them architecture students) were committed to make an art free of pretension and artifice. Their idols included Munch, Gauguin, Dostoevsky, Freud, Ibsen, Strindberg, Wedekind and Nietzsche. Bearing this in mind, it is not surprising that exponents of Expressionism later found points of commonality with National Socialism. The admiration was reciprocated by some senior Nazis. However, it was the supporters of traditionalism among the Nazis who won out, consigning Expressionism to the category of entartete Kunst (“degenerate art”) when it came to the selection of official art styles after 1933.

Brücke was dissolved in Berlin in 1913. Blaue Reiter (“blue rider”) functioned as a Munich-based avant-garde group from 1911 to 1914. The Great War shattered the utopian aspirations of these artists; in some cases, the artists were killed in combat. We find in the Neue Galerie collection the proto-abstraction of Franz Marc and the cross-over art of Vasily Kandinsky of the 1910-3, which blends symbolism and abstraction. Blaue Reiter is discussed in the light of theosophy and spiritualism, which would become a lesser-considered strand of art teaching in the Bauhaus, particularly under Johannes Itten. An essay assesses the responses of artists to the Great War. These varied greatly, ranging from absolute pacifism to militaristic chauvinism. The post-war art of George Grosz and Otto Dix blends fierce satire with a seeming appetite for degradation; the impact of their work comes from that combination, which betrays a crucial ambiguity. As more perceptive critics of the time noted, an artist could not lavish so much care and time on art that was wholly condemnatory.

Austrian Expressionism – in its best in Schiele, Oskar Kokoschka and Richard Gerstl, all of whom are represented by good examples – are marked by their engagement with the psychology of the subject rather than meditations on urban life or the condition of primitive man. There are few extant paintings by Gerstl, because Gerstl destroyed most of his paintings and drawings before committing suicide. The Neue Galerie owns four canvases by Gerstl, two of which (a self-portrait and a portrait of a seated man) are very fine pieces. We should mourn the loss of an artist, at the age of 25, capable of such work. The multiple nails in the coffin of German Expressionism were the advent of Dada, Neue Sachlichkeit and the scientific abstraction of the Bauhaus. Dada and photo-montage is represented in less depth than other movements in the collection.

It is instructive to compare WW designs with those of the Bauhaus, founded in Germany in 1919. Bauhaus extended the line of stark Modernism but without the influence of Art Nouveau, substituting the influence of strong unmodulated colour forms found in De Stijl abstract art. Bauhaus sacrificed functionality for style sometimes. The seats are often cruelly uncompromising for the human anatomy. Although the director Walter Gropius sought to fuse architecture, fine art and applied art – including clothing – in a manner that would be harmonious and pleasing, the Bauhaus never managed to balance its stated aims. The subsequent director, Hannes Meyer, deliberately steered the Bauhaus towards a more overtly socialist end, citing “the needs of the people rather than the requirements of luxury”. Meyer later moved to the USSR to teach, putting his socialist views into practice.

There are chapters covering Expressionist cinema, photo-montage, Klee teaching at the Bauhaus, the decline of artistic freedom in Germany and persecution of artists under the Nazis. This last includes the story of Felix Nussbaum, which is becoming better known over recent decades. Nussbaum was an artist of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement, who was imprisoned in France as an enemy alien in 1939. He later left the camp and went into hiding in Brussels, but he was ultimately captured by the occupying Germans and sent to a death camp. His wartime art portrays the artist in the French camp and gives an idea of what Jewish artists might have painted in the concentration camps, had they had access to materials.

The collection is wonderful but incomplete. Without the work of some traditionalist, National Socialist and Communist artists, we get an uneven view of art of Germany and Austria from 1890 to 1940, even of Modernism. Art of National Socialism and (pre-war) Communism were reactions against Jugendstil and Weimar-era Modernism. The Neue Galerie is a private collection and therefore subject only to the taste of the owner, who determines what is part of his conception of this history, but the story of Germanic Modernism cannot be properly understood without the inclusion of art that has hitherto been dismissed, seemingly without due aesthetic and historical consideration.

Preconceptions surface in the catalogue essays, mainly to do with the politics of today being applied to a period now a century past. The translation of völkisch as “racist-populist” is not accurate; it means “of the people or kinfolk”. Affinity for the company or culture of one’s own race does not necessarily imply sentiments of racial superiority, contrary to the translator’s assertion. Berating of individuals for sexism (as found in the essays by Janis Staggs) is unhelpful. The history of the operation and circumstances of WW and Bauhaus do have a sex dimension, but Staggs is not the author to apply a dispassionate eye.

Modern Worlds is an excellent, serious and lavishly illustrated survey of Modernism in Germany and Austria, forming an ideal counterbalance to art histories that prioritise the French lineage of the Impressionism-Pointillism-Fauvism-Cubism line. This book is a fitting tribute to the vision and commitment of Ronald S. Lauder (and Serge Sabarsky) and provides a fascinating slice of cultural history.

[i] Olaf Peters, “Degeneration and Empire”, p. 33

[ii] Olaf Peters, “Brücke”, p. 235

ALEXANDER ADAMS is an artist, art critic, novelist and poet. His most recent book is Artivism: The Battle for Museums in the Era of Postmodernism (Societas/Imprint Academic, 2022)