RICHARD DOVE revels in Akhnaten at the ENO

“The thing about Philip Glass is that there’s so much repetition.” A friend pronounces his verdict. Well, yes, but what repetition. The ENO revival in association with LA Opera with the third of Glass’s so-called ‘portrait’ operas, Akhnaten, is entrancing. The set is a multi-level tableau of slow-moving interpretation and quite a bit of juggling. The jugglers are there to symbolise, I think, an imposition of order on the chaotic religious miasma that was ancient Egypt. King Amenhotep IV succeeds his father and declares a monotheistic religion with him, unsurprisingly, at its pinnacle.

The music swoops, swirls and glides across the narrative with the singers seeming to provide accompaniment for the orchestra and vice versa.

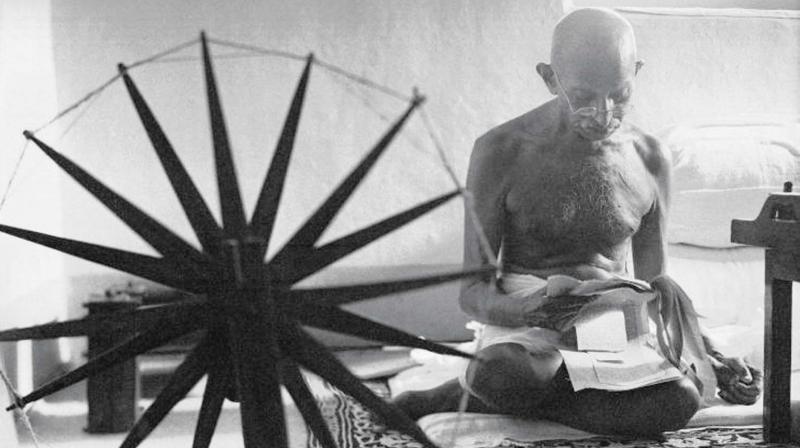

Glass had to do shifts as a New York taxi driver alongside regular plumbing jobs to help fund (and subsequently pay for production losses) his first portrait opera, Einstein on the Beach, which he developed with the grandiloquent imagination of Robert Wilson. He began by performing in sparsely attended recitals in New York lofts. Slowly, opera houses around the world caught up with Philip Glass. His second portrait opera on Mahatma Gandhi, Satyagraha, was a resounding and enduring success.

Akhnaten is now almost 40 years old and Glass has moved from the fringe to the mainstream. He is now chauffeur-driven.

American counter tenor Anthony Roth Constanzo has made the role of Akhenaten his own, appearing in productions in 2016, 2019 and now in this revival. He shows no signs of weariness with the role, commanding the huge stage with his soaring voice and subtle, precise gestures. His wife, Nefertiti, is an equally commanding presence, with mezzo soprano Chrystal E Williams delivering power and gravitas.

Phelim McDermott’s production is bold and sometimes a little baffling when images override meaning – a sort of Zoolander moment or two amidst the creative visual excellence.

The Coliseum was packed for the performance – ENO at its very best. The attempt by the Arts Council to shift it out of London is gesture politics at its most egregious. Let’s have more ENOs in Lincoln, Newcastle, Plymouth as well as London. We all need doses of cultural excellence, as bills mount and services decline.

The audience is wonderfully diverse and soundly engaged despite the singing in Egyptian, Hebrew, Akkadian and English. You do not need surtitles to get the gist. We are now well attuned to small dictators marooned in gilded palaces. It was only in the late nineteenth century that the remains were discovered of the city Amarna built by Akhenaten. In 1907 a mummy was unearthed that is most probably Akhenaten. The body was effeminate with womanly hips, elongated skull and fleshy lips, giving rise to speculation that he suffered from rare diseases. His androgynous appearance is cleverly portrayed in the opera. Akhenaten, the Sun King, is variously described as enigmatic, mysterious and revolutionary as well as mad and possibly insane. This production captures all those contradictory passions in a magisterial sweep. It is certainly repetitive but gloriously so. I will let my friend know.

RICHARD DOVE writes from Kent