DEREK TURNER remembers Andalusia

I started awake as the plane came into land. The cactuses along the edges of the runway suggested even to my stupefied senses that we were no longer in Birmingham. Distinctly un-English heat fell heavily on our heads and draped itself around our shoulders as we walked into the terminal below the giant, magic word, “Sevilla.” As our taxi whizzed along the Avenida Kansas City into the long sought-for metropolis, we moved surreally sideways in culture, space and time.

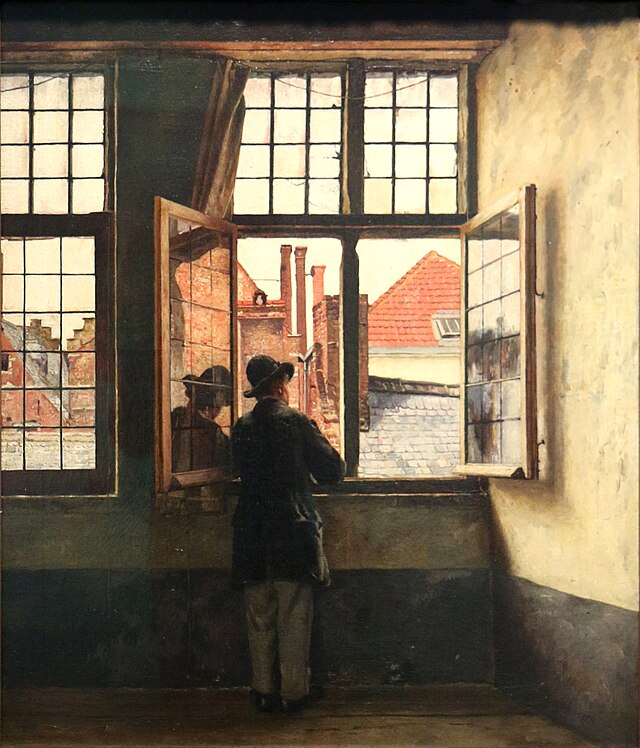

Once established in Seville’s old town, we ventured out for a first foray into a streetscape which had not altered in its essentials for several centuries – narrow calles, often cobbled, lined with white several-storeyed houses, with a whiff of drains, interspersed with baroque churches of gilt-encumbered altars, wounded Jesuses and weeping Virgins.

In August, these churches are eerily expectant, open only briefly in the evening, lavish theatrical sets for rare individual worshippers. It is hard to visualize them in Holy Week, when they thrum with eldritch energy, as hundreds of pointed-hooded ‘penitents’ parade monstrances and lurid Passion tableaux into the streets under the regard of thousands – phone-pressing tourists of course, but among these also true believers, witnesses to a faith that still subsists in this land long ago hard-won from Islam.

Wilting after our early start, and unaccustomed to 38˚heat after an English summer hitherto notable only for its almost complete absence of sunshine, we dined gratefully on Greek salad in the Alameda de Hercules, under the gaze of the Greek god and Julius Caesar standing on the tops of Roman columns – statues of the mythical founder of the city, and the emperor who gave it its first urban statute.

Seville is ancient indeed, its locale inhabited by ‘Celtiberians’ at least a millennium before Christ, who founded a town called El Carambolo (later absorbed into Seville’s western suburbs) and traded in precious metals mined in the hills around. Greeks and Phoenicians came to trade in copper, silver and gold, and some settled along the banks of the broad river then called the Tartessos.

The Phoenicians’ settlement was called Hisbaal (a reference to their deity Baal) or Spal, the dankly powerful remnants of which underpin one of Seville’s latest landmarks, built between 2006 and 2011 – the huge wooden structure (perhaps the world’s largest) nicknamed ‘Las Setas’ (The Mushrooms) because of its shape, from the top of which on an August afternoon there are near-blinding views of the brilliant-white contemporary skyline.

The Romans took Spal from the Phoenicians’ Carthaginian successors (Hannibal’s wife is said to have come from this area), and dubbed it Hispalis – although their chief settlement hereabouts was the colony of Itálica, founded by Scipio, whose well-preserved ruins are just northwest of the present city. They renamed the Tartessos the Bætis, and the surrounding province of Hispania Ulterior (later Hispania Bætica) became prosperous and prestigious, with Emperors Hadrian and Trajan both born in Itálica (possibly also Theodosius) – and the poet Martial a long-time resident, who interestingly records seeing castanet-clicking Tartessian dancers some seventeen centuries before the word ‘flamenco’ was first recorded.

The name Andalusia comes from the Arabic term for the entire Iberian peninsula, al-Andalus, ‘land of the Vandals’ – a reference to the Germanic tribe that overran Iberia after the fall of the Western Empire, and then fought enthusiastically among themselves. One eighth century Visigoth kinglet had the bright idea of requesting military assistance from nearby North Africa, within view just across the Pillars of Hercules. Like many an importer of mercenaries before and since, the unhappy kinglet then found himself unable to get his ‘guests’ to go.

From 711 onwards, Moorish armies surged across much of present-day Spain and Portugal, and famously menaced even France, before ultimate downfall more than seven centuries later, in Europe’s pivotal year of 1492. The Moors were more than formidable fighters; they were also agricultural innovators, instigating impressive irrigation schemes and introducing lemons and the oranges with which Seville is now synonymous. They gave the Tartessos/Bætis its ‘final’ name, Guadalquivir, derived from the Arabic for ‘wide river,’ erected some still-extraordinary edifices and presided over some highly cultivated courtly cultures which both perpetuated Greek learning and encouraged new intellectual experimentation (within certain politic limits).

Moorish Andalusia is often adduced as an historical example of ‘tolerant’ Islam – a rhetorical counterpoint to other portrayals of Islam as a narrow-minded and rebarbative force bent on global domination. One suspects this is overdone; many of the Christians and Jews who lived under Moorish suzerainty cannot have seen their situation so sunnily. They were subject to heavy special taxes, and there would have been daily indignities. Even by the standards of the early Middle Ages, the annual tribute of one hundred Christian virgins to the Moorish monarch must have grated, while the most tendentious Moorish apologist cannot deny the frequently vicious internecine conflicts of the courts. Some Moorish dynasties were ostentatiously brutal, like the 11th century Abbadid ruler who ‘decorated’ his forts with flowers planted in the skulls of enemies.

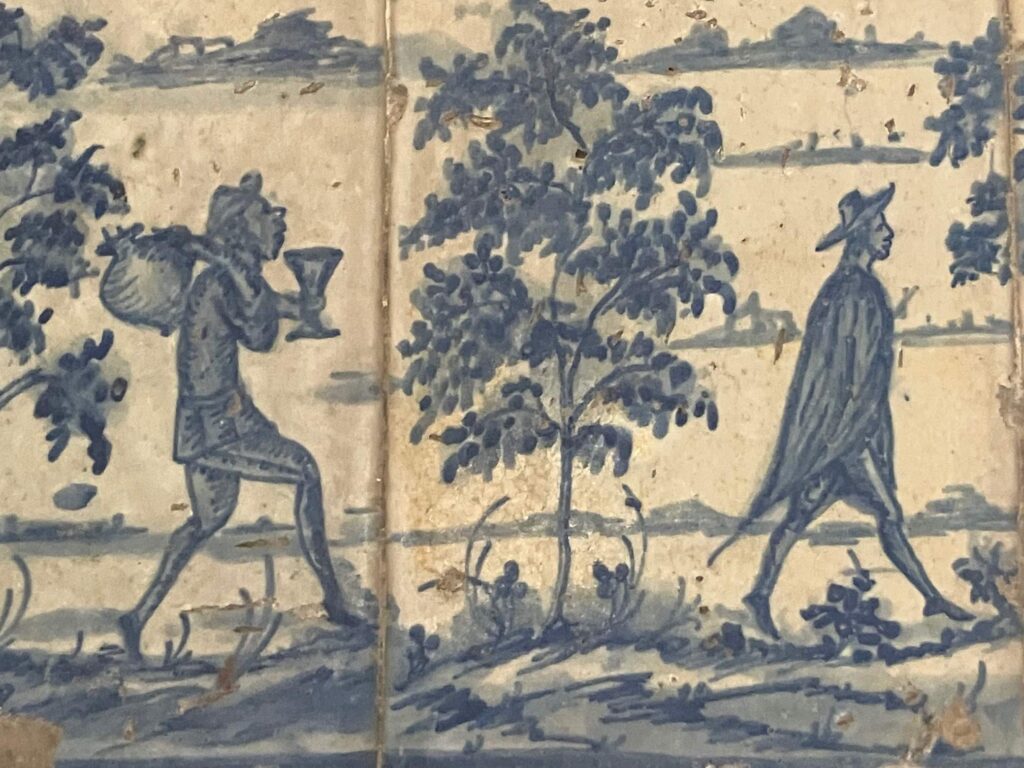

Moorish influence is nevertheless everywhere to be seen in southern Spain, and indelible – from the domes and arches of former mosques, and the characteristic castellation of their forts, to the plashing fountains in private courtyards that afford psychological as well as visual relief amidst August’s punishing heats. The Mozarabic Christians living under and influenced by Islam were later mirrored by the Mudéjar Muslims living under and influenced by Christianity, and their cultures run into each other in all kinds of ways – from architectural styles and the colourful azulejo tiles for which modern Spain and Portugal are noted, to cuisine and language. Even the Spanish national hero known as ‘El Cid’ – the eleventh century warrior Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar – fought both with and against Moorish forces, depending on circumstances. Andalusia’s still notable Christian ardency may also be a paradoxical legacy of Islam – its defensive fervency a reaction to humiliating centuries of second-class status.

It is probably impossible to separate ‘Moorishness’ from a more generic ‘Mediterranean’ culture, where modes of living on all coasts have always borne similarities, because of the shared climate and geography on top of millennia of intellectual or more violent interactions. But there is ‘un-European’ exoticism to be found in the culture of Andalusia – a culture which for many outsiders has become a kind of shorthand for all of Spain. Specifically Andalusian traditions such as flamenco, bull-fighting, and tapas – as well as its arid, olive-treed, ruined castle-dotted landscapes – have become stereotypical images of the whole country, which must surely irk many Aragonese, Asturians, Basques, Castilians, Catalonians, and Galicians.

The Moors, so long militarily dominant, eventually became etiolated – divided among themselves, and some of their rulers possibly too ‘civilized’ to worry about their frontiers. Burgeoning Christian kings of an increasingly self-conscious and gradually coalescing Spain placed ever-growing pressure, and Seville was retaken by the Christians in 1248. In 1492, the last Moorish ruler in Spain, King Boabdil of Granada, was forced to hand over the keys of the Alhambra – famously weeping as he looked back on Granada for the last time, for which his mother rebuked him, “You do well, to weep like a woman for what you failed to defend as a man!”

Seville’s most expansive days were now to come, as it became first the launching pad of epic expeditions, and then chief port for the Spanish Empire, safely upriver from dangerous Barbary corsairs, but with easy access to the Atlantic. Audacious navigators set off down the turtle-haunted waterway, most celebratedly Columbus, who may have been Italian but had a crew made up largely of local men. A modern statue of one local boy, Rodrigo de Triana, stands in the Triana riverside district, his plinth bearing the laconic inscription “Tierra!” (Land!) – the single word he shouted when he was the first to espy the Americas.

Magellan’s equally world-altering expedition set out from here in August 1519, five tiny (approximately 50 tons) carracks like the Victoria, tasked with finding a western route to the spice islands. The Victoria was the only one to return, in September 1522, the first ship to circumnavigate the world. Magellan had been killed in the Moluccas, and the Spanish are proud that it was one of their own, the Basque captain Juan Sebastián de Elcano, who completed the voyage. As he wrote in his none-too modest memoirs, “I was the first to close the globe in my wake…my journey has become a legend.”

A seaworthy replica of the Victoria – harbinger of whole Indies fleets – is tied up alongside at Seville, beside a small museum explaining something of the context and consequences of that world-changing voyage. Coloured late fifteenth century portolan charts show fairly carefully inked coastlines as far north as Britain, as far south as the Cape of Good Hope and all around the Mediterranean littoral – but blank or simply sketched spaces almost everywhere else, conveying the immensity as well of excitement of the navigators’ tasks.

The Golden Tower nearby, which was once used to store the vast treasures brought home from the Americas, now holds a small naval museum, in which the achievements of earlier Spanish sailors are linked proudly to the modern navy. By the late sixteenth century, Seville had become fabulously wealthy, with a population of over 150,000. Between the 16th and 18th centuries, the Spanish controlled an estimated 80% of the world’s silver, mined in South America (Argentina is named after the Spanish word for silver).

A less well-known commodity was cochineal, which arrived in Seville by the shipload (in 1587 alone, an estimated 72 tons – equivalent to over 10 billion beetles), and sold on under Spanish monopoly – dyeing the famous velvets of Venice, crimsoning cardinals’ robes across the Catholic world, and even Buddhist temples in Siam. This is not to mention Spain’s long domination of the tobacco trade – symbolized in Seville by the Antigua Fábrica de Tabacos, where Bizet’s gypsy Carmen rolled cigars and dreamed of her toreador.

In Spain – at least, in Andalusia – there is little public evidence of the angst presently eating at other Western countries with colonial pasts. To make an anecdotal but possibly not wholly worthless point, many obvious tourists as well as residents (we met Seville residents from Colombia and Venezuela) appear to bear Mesoamerican physical traces, suggesting not just the length of these connections but also an ease with them. Road names and statues referencing the Empire remain sturdily in situ, and buildings like the many national pavilions built for 1929’s hugely ambitious (but unluckily-timed) Ibero-American Exposition retain their original names. Evocative documents like the crew lists, cargo manifests and royal charters of globe-redrawing expeditions are guarded by serious-faced security at the Archive of the Indies, beside the Cathedral. Epic imperial undertakings are almost as intertwined with Spanish identity as Catholicism.

Inside the Cathedral – built on the site of a grand mosque, and the world’s largest church by cubic area – is the late 19th century tomb of Columbus designed by the sevillano sculptor, Arturo Mélida. This was originally intended for the cathedral at Havana, but was erected here instead after the Spanish-American War showed Spain’s imperial glory-days were finally over. Columbus’s coffin (which may not actually contain his remains, which were moved several times) is upheld by four imposingly inhuman figures, symbols of the kingdoms of Aragón, Castile, León and Navarra. The lance held in Castile’s free hand once impaled a secondary symbol, a pomegranate – Granada in Spanish, a lapidary insult to the last of the Moors.

The main surviving part of the old mosque is the Cathedral’s bell-tower, the Giralda, which was once the minaret. Those uneasy with such old Christian triumphalism ought to recall that the mosque itself had been a triumphalist structure, symbolically built on a base of smashed Roman statuary. The Giralda – named after its sixteenth century giraldillo (weather vane) – is now the stereotypical symbol of Seville, seen everywhere on tourist ephemera, and more lastingly in the many old paintings seen around the city, showing the city’s two patron saints, Justa and Rufina, upholding the tower to prevent it falling during the Great Lisbon Earthquake of 1755. The Cathedral displays a fine Justa y Rufina by Goya – although the most famous painters associated with Seville are Murillo, Velázquez and Leal, all born in the city, with plentiful examples of their works on display in churches, museums and former palaces.

The most beautiful artwork in the Cathedral itself is undoubtedly the altarpiece designed by the Flemish carver Pieter Dancart, which was begun in 1482 and took 80 years to complete (the Spanish controlled all or most of modern-day Holland and Belgium between 1556 and 1714). Showing 45 scenes from Christ’s life, it is the world’s largest altarpiece at almost 90 feet high and 72 feet wide, and is coated with an estimated three tons of gold. The Spanish love of precious metals also extends to silver, with the word “Plateresque” (‘in the manner of a silversmith’) coined to describe first Spanish, and then any architecture, of the 15th-17th centuries that combines Gothic proportion and scale with especially ornate or flamboyant designs.

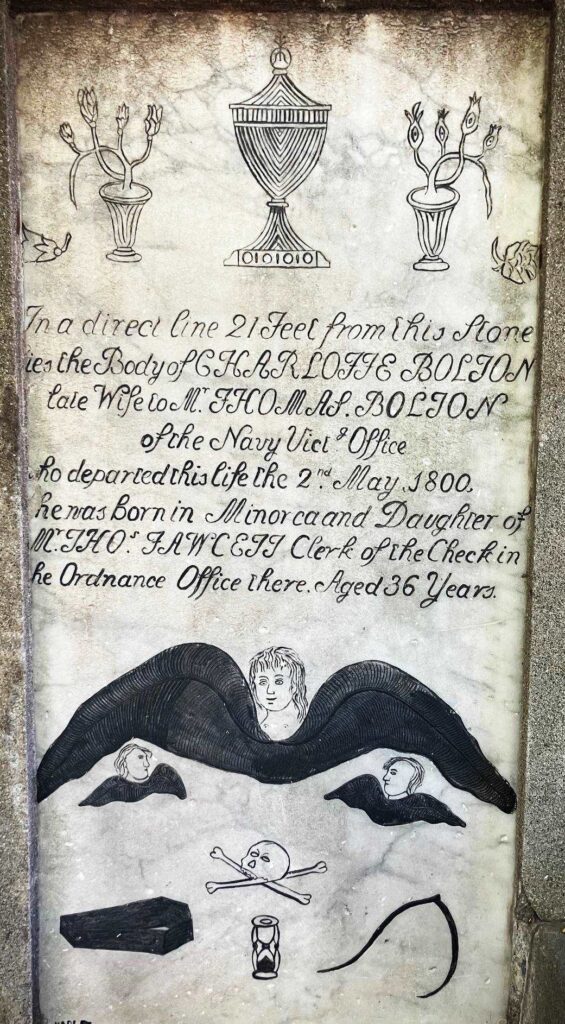

The ponderous lugubriousness of the Spanish brand of Catholicism is everywhere evident in Seville – perhaps most searingly in the Hospital de la Caridad, founded by Don Miguel de Mañara (1627-1679), and completed in 1674. Mañara had been a notorious youthful libertine, until one day he had a terrifying ‘preview’ of his own funeral procession. Shaken to his soul by this ‘sight’ (and an outbreak of plague, which killed thousands of Sevillians), he joined a local brotherhood, whose avocation it was to inter the bodies of criminals, plague-victims and vagrants, and used his family fortune to found the Hospital for the relief of the poor and dying – for which it is still used. Dignified venerable men saunter in and out of the stately complex, or sit outside the front in short-sleeve shirts, composedly awaiting destino.

The Hospital’s magnificent chapel was decorated by eight paintings by Murillo, and four of his works are still here; the others, looted by the French during the Peninsular Wars, ended up ecumenically in London, Ottowa, St. Petersburg and Washington. There are also two striking paintings by Leal, on the theme of the Triumph of Death – one showing a trampling skeleton pointing to the words In ictu oculi (‘in the blink of an eye’), and the other, inscribed Ni más, ni menos (‘no more, no less’), showing a rotting coffin and a decomposing bishop so gruesomely realistic Murillo marvelled “you have to hold your nose to look at it.”

Mañara himself decomposes in the crypt, although his stone was set at his request in the chapel’s doorway so it could be stepped upon by all comers. He also left a small body of disconsolate writings, translated as Discourse on Truth. Here is a characteristic extract:

Seek out Alexander, call for Scipio, and perhaps their ashes will be in some mud wall or in the soil of a garden…Who would believe that the body of Julius Caesar, whom the whole world feared, is now growing cabbages in an orchard?

From Seville’s Roman fathers, Mañara came even closer to home:

Consider a vault; enter it with consideration, and set yourself to looking at your parents, or your wife (if you have lost her), or the friends you knew; consider the silence. Not a sound is heard; only the gnawing of the maggots and the worms can be heard. And where is the noise of pageboys and lackeys? Everything comes there; observe the jewels of the palace of the dead: some spider webs.

Upstairs in the Hospital’s hot, still and silent treasury, possibly overcome by the horror of the human condition, a security guard dozed at his desk.

Alcazar is another word derived from Arabic, and examples may be found in many Spanish towns. Seville’s Alcazar is one of the best known and largest of these citadel-palaces – begun in the eighth century on the site of a Roman barracks, and later strengthened and adorned by the Abbadids, and then the 12th/13th century Almohads. The Alcazar we see today is however mostly a Christian construction, begun not long after 1248. King Pedro I of Castile and León (r. 1350-69), amusingly nicknamed both “The Cruel” and “The Just,” carried out major reconstruction cannibalising other Moorish buildings, and much of this is still visible today.

Pedro was certainly capable of cruelty, notoriously murdering the Archbishop of Santiago – and, here in the Alcazar, his own cousin (Pedro himself was later murdered, stabbed to death in a tent). On the other hand, he generally protected Jews, merchants and peasants, and sided with the Moors on occasion. One emir gave him an enormous ruby as reward for assistance rendered, which ended up in the English Crown Jewels. The English took Pedro’s part in the Castilian Civil War of 1351-69, the Black Prince personally helping him win the Battle of Navarette of 1367. Two of the daughters Peter had with his pulchritudinous mistress, María de Padilla – so beautiful it was said courtiers vied to drink her bath water – married sons of England’s Edward III, so becoming wives to the first Dukes of both York (Edmund of Langley) and Lancaster (John of Gaunt). He is honoured in Chaucer’s ‘Monk’s Tale’ – “O noble, O worthy Petro, glorie of Spayne.”

Back in Pedro’s dream-palace, there are marble-columned windows, arched and vegetation-shaded verandas, pierced pendant friezes and fretwork and overhanging rooves, and syncretical juxtapositions, with Christian lion symbols ‘guarding’ the gates, and Holy Roman Emperor Charles V’s personal motto Plus Ultra (‘Yet Further’) appearing on walls near older Kufic inscriptions still lauding Allah. The frantic and repetitive geometric patterning of Moorish wall-tiles seen here and in many other places strongly suggest artistic frustration of not being allowed to depict figures; beautiful though the tiles undoubtedly are, they offer little human interest.

Through a great door to the right is the Salón del Almirante, named in honour of Columbus’s official title of Gran Almirante (Great Admiral). In this suite of rooms, Columbus, Balboa and others discussed and plotted some of the earliest American voyages, and changed the world. In the Capilla de los Navigantes, a striking 16th century altarpiece shows the Virgin protecting precisely-drawn Spanish ships under her cloak, as well as Columbus and Charles V.

Outside, sun-punished brick walls and Roman-to-medieval columns surround green rectangles of water gulped by goldfish, while red dragonflies oviposit eggs doomed too to be engulfed. Tourists wearing alarming ensembles sip endlessly from plastic bottles, dutifully press audio-guides to moisture-beaded ears, and photograph themselves with fountains. Green parakeets make a similar chattering commotion high up in the crowns of palm trees and among the prickly pear and rosemary, and higher still screaming swifts dash in search of dipteran dinners. Choruses of cicadas chirr and click halfway-down, and ground-level grasshoppers perform prodigies of propulsion flying from your feet. Blackbirds bounce across browned grass, sparrows spik in verdant box-hedges, and geckos charge up the plinths of classical heroes.

Trees are among the chief adornments of southern Spain, valued by enlightened planters over the centuries not just as shelter-givers and food-providers, but often for their own sakes. These trees come from everywhere – Africa, Asia, the Americas and even Australia – planted by botanical benefactors but now abundantly naturalised in this country which scarcely knows snow. Cypresses and pines define boundaries, and mark out classical prospects. Oranges and lemons aromatise and stud even the severest streets, offering festive-hued fruits among arsenic-green foliage. Three-hundred-year-old planes peel picturesquely and susurrate in public squares. Bays and laurels offer flavours for gazpacho, and evergreen crowns for victors. Almonds, avocados, bananas, figs, pears and pineapples prosper in gardens and parks. Enormous rubber trees with writhingly restless trunks spring dynamically skywards and drop hard small seeds with a clack onto the pavements. Cactuses stand stark as skeletons, and palms like punctuation marks, their fronds often fondly intertwined in city balconies by those recalling Christ coming to Jerusalem.

The Holy City comes to mind again not far from the Alcazar, in the Casa de Pilatos – ‘Pilate’s House’ as conjured by the Marqués de Tarifa upon his return from Jerusalem in 1519, where he was said to have seen the study in which the Roman decided the Galilean’s fate. A charmingly anachronistic ‘replica’ of this room stands within a ducal home rich in realer antiquities, including a statue of Athene that may go back to the fifth century BC. Black and white mosaics and reflecting fountains cool down courtyards, and creeping plants climb vermilion walls towards unbroken blue. A column in the chapel is supposed to represent the one at which Christ was flogged at Pilate’s order. Another Rome-recalling tradition tells of an orange tree in the garden sprouting from the spot where a servant unthinkingly dumped the ashes of the Emperor Trajan.

Out beyond the city limits, old olives define the rustic scene, twisted veterans of countless droughts somehow still standing on red earth and endlessly recirculating dust, offering oils for the people and shade for black belligerent bulls. Holm oaks shed acorns for the long pigs whose desirable dried jamón hangs from hooks in supermarkets and delicatessens alike, sweetened and wizened from air-curing, or stained by old smokes.

We come into Cádiz – which claims to be the oldest city in Europe, founded in the second millennium BC – from the north, along an equally venerable highway. Navies of Carthage, Rome and Spain were stationed here, and still are – sleek grey frigates visible from the road, elegantly dangerous presences among the Atlantic haze (it is also the base of the US Sixth Fleet). Its strategic importance attracted unwelcome English attentions often during England’s long wars against ‘the Don.’ In 1587, Drake made havoc in the harbour, ‘singeing the king of Spain’s beard’ as he exulted to Elizabeth, provoking the metaphorically scalded Spaniard to launch the following year’s unlucky Armada. In 1596, the Earl of Essex did more singeing, and Nelson in 1797.

Cádiz shimmers with sea-longing, poised perfectly on the very edge of Europe, every azure horizon beckoning to adventure. A botanical garden along the front contains rare trees from as far away as the Antipodes, and huge cruise ships bulk along the seafront. We raced across burning beach sands to plunge into welcome waves, among tourists but also natives (gaditanos) – a very ‘continental’ blend of highly respectable matrons in voluminous one-pieces, and tattooed and topless young. Salt affects the very stone of Cádiz, coating, pitting and weakening buildings, including the austerely grand Cathedral, which towards the end of the 20th century began weeping stone onto the congregation.

We downed paella in the plaza before the Cathedral, the sun refracting through soap-bubbles blown by a children’s entertainer. Small children chased these sprites across the square, while a saxophonist playing pop excited epidemic chorea among slightly older tourists, with groups of up to 50 dancing along despite the heat. It seemed appropriately Saturnalian in a city celebrated for exuberant Carnaval.

The Cathedral crypt contains the remains of Manuel de Falla, born in Cádiz in 1876, composer of Nights in the Gardens of Spain and most famously, El Amor Brujo – notes from which sound out upon the hour from the clock of the town hall. His cantata La Atlántida is inspired by the view of the Atlantic from Cadíz, and the tenth of Hercules’ Twelve Labours, the task of capturing the cattle of the three-bodied monster Geryon, whose island of ‘Erythia’ is identified with this area.

As well as evocative, the city is elegant and prosperous, chic with 19th century promenades and smart restaurants, and famously liberal in its politics. In 1812, the Cortes of Cádiz was set up as the first Spanish parliament which aimed to represent all classes, and all parts of Spain and its dependencies. It ratified the Constitution of Cádiz, Spain’s first constitution (and one of the world’s first written constitutions) – which established the country as a constitutional monarchy under Joseph Bonaparte, theoretically with almost universal male suffrage and a free press. It was suppressed just two years later, after the French had been expelled and Fernando VII restored – at the urgent demand of the populace. That Constitution is now, arguably ironically, seen as something of a democratic landmark.

In 1832, the American writer Washington Irving published his fourth book on aspects of Spanish history, Tales from the Alhambra. The bestselling author of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow and Rip van Winkle had been much influenced by Walter Scott, and it shows in all his Spanish works, which range from highly romanticised histories to straightforward historical fiction. He sparked a huge interest in what had long been an overlooked era, in a poor part of a declining country. He was besotted with Spain, which he had first visited in 1826 while attached to the American Embassy, and saw the Alhambra as the country’s mystical heart. Granada in particular captured his imagination, and he had already published The Conquest of Granada (1829), which fictionalised the centuries-long struggle which ended in 1491, with the capitulation of Boabdil the Unlucky. As he wrote in Tales, “To the traveller imbued with a feeling for the historical and poetical, the Alhambra of Granada is as much an object of veneration as is the Kaaba or sacred house of Mecca to all true Moslem pilgrims.”

He spent several months in the dilapidated and war-damaged old fortress, in a state of exaltation, sleeping fitfully in former palatial apartments and breaking fasts in the celebrated Court of the Lions. His panegyrics encouraged other writers to come, and so ineluctably today’s tourists, who descend on the town by the million each year.

The 2023 edition of Rough Guide to Andalucía waxes Washingtonian in calling the Alhambra “the most exciting, sensual and romantic of all European monuments.” But were Irving to visit now, he would find it stripped of most of its melancholy mystique, erased by sheer numbers of sightseers – including, of course, ourselves! But it is still a highly suggestive silhouette in reddish stone – a place seemingly worth toiling towards although on top of a steep hill, even at noon in August when the sun beats back up at you from the flinty cobbles, and even the trees have been stunned into stupor.

There was a Roman settlement here, which the 711 invaders renamed and reused, but it was always less important than Cordoba. It was not until the 1240s that Granada would become prominent, and over the next 250 years ever more precious to the Moors as their other kingdoms went under one by one. Most of the present complex dates from the middle of the 14th century, when the Emirate was at its apex.

By 1491, Granada was the last Muslim state in Europe, and embroiled in civil war even as Fernando and Isabella’s forces encircled the city. After a ten-month siege, by November all was over, and Boabdil’s vizier handed over the keys to the fortress on 2 January 1492. Boabdil was granted an estate not far away, but the same year left Spain forever, along with many other Muslims, and he died in Morocco in obscure circumstances sometime between 1518 and 1533.

The Christian monarchs treated Boadbil and his retinue chivalrously, but a triumphal reaction was inevitable from the moment their silver cross banner first fluttered from the fortress’s ramparts. They converted the last of Spain’s mosques into churches, and stipulated the expulsion or forced conversion of Spain’s Jews, and then those Muslims who hadn’t left, understandably regarding them as a potential fifth column.

Fernando and Isabella lived and worked in the Alhambra for some time – it was allegedly at the Alhambra that Columbus first broached the idea of sailing west in the hope of finding India – and they are both buried in the city, in the nearby Capilla Real. This is a moving building in its own right, where the monarchs’ unpretentious lead coffins may be glimpsed (but not photographed) through the gate of their vault below their showier effigies above. The sacristy contains central national-religious relics that still radiate romantic force – Fernando’s sword, Isabella’s crown, and even the banners that flew on 2 January 1492.

Back at the Alhambra, Fernando and Isabella’s grandson Charles V built a Renaissance palace (now containing an excellent late medieval art collection) by demolishing one of the palace’s wings. Napoleon’s troops wreaked terrible damage between 1812 and 1814, and planned to destroy the whole complex on their retreat, but a crippled Spanish patriot (and benefactor of all humanity) named José García removed the fuses. What remains after these vicissitudes is as beautiful as it is stately.

Visitors enter through the remains of the 13th century Alcazaba, a fortress built on top of an earlier fortress. There are stupendous views from the Torre de le Vela (Tower of the Bell) down over the Rio Darro, the vast white-brown vega, and the stage-set-like Sierra Nevada, whose peaks in winter can be capped with snow. This is a landscape of the grandest proportions, that might have been designed equally for acts of great chivalry or acts of great cruelty. Many famous Western films were made in central Spain, to transfer the toughly uncompromising psyche of Spain to even more epic vistas.

A garden softens and sweetens the senses, an ordered paradise of creepers, myrtles and roses – leading to the Palacios Nazaríes, a strange confection to find amid such mighty walls. Built quickly, and intended partly as a pleasure house, the suite of splendid rooms is decorated with Islamic calligraphy and motifs, below which successive rulers held court, conducted business, received guests and relaxed. In the case of Yusuf I (1333-54), it was also a place to die, the sultan stabbed to death while he prayed.

The harem is approached through Irving’s favourite Court of the Lions, named for the twelve stylized beasts supporting the fountain, which, an ingratiating inscription insists, are held in check only by their respect for the sultan. The Sala de los Abencerrajes has a ceiling of almost impossible ornateness – a sixteen-sided dome with frothy stalactite tracery and high windows covering a reflecting fountain, the delicately incongruous scene of an atrocious if apocryphal crime, when a sultan is said to have murdered 16 members of the Abencerraj family.

A set of atypically Islamic figurative portraits look down on the Hall of the Kings, followed by the domed hall of the favourite wife, and the quarters of all the others, ending in the Royal Baths, where sultans and sultanas would disport themselves to the strains of blind singers. At the end we reach the geometrical gardens of the Generalife, a high-up demi-paradise for fretful Berbers, a place to watch festive fireworks, stroll away the cares of state or plan a tryst, under the guardianship of great walls and the gaze only of eagles.

We hired a car and headed north from Seville to see family, grateful to swop ring-roads for ever emptier highways. We were heading for Iberia’s parched and less-known heart, and the borderlands of Extremadura. Quiet roads, and even quieter fields – mile after mile after mile of olives, oaks and thorn trees, mile after mile after mile of thirsty terrain stretching to blue and purple distance or unreal mountains, the whole expanse almost without movement, except for rare and vast birds of prey gliding along on baking thermals – griffon vultures, coldly viewing the campo, Roc-reminiscent even in the distance, their very name suggesting fabulous creatures.

Armies have marched and counter-marched this way since always, trudging sandals or boots caked with dust, sweating and swearing in armour or uniform, from the Romans via the Visigoths, Moors, Christians, Wellington’s Britons and Soult’s French, up to Franco’s ‘Army of Africa’ who in 1936, in an early setback for the Republic, took the town of Mérida – our first stop outside Andalusia, and one of the most impressive Roman sites in a country with many such.

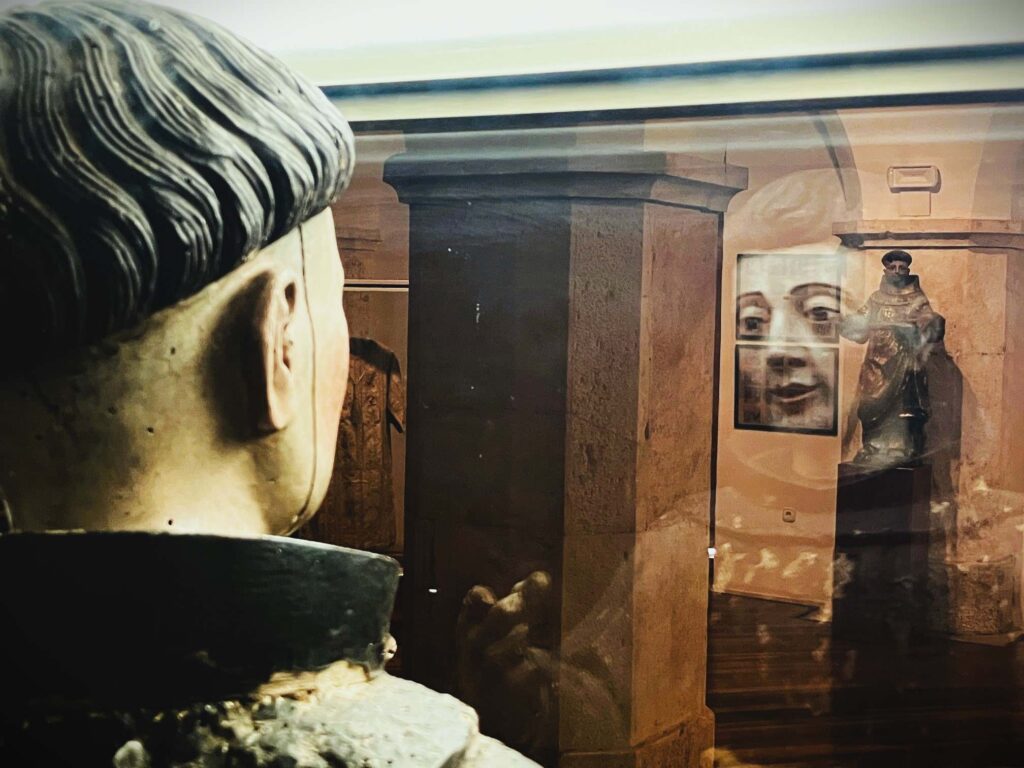

Founded in 25 BC, its original name of Augusta Emerita indicates its importance as imperial foundation, and nature as colony for ex-soldiers. It was one end of the Silver Way, the Roman road that ran to the mines of the south, and became capital of the province of Lusitania. Its aqueduct, bridge, triumphal arch and theatre are wonderfully complete, and the columns, walls and other features that are found in unexpected places all over town suggest much remains to be uncovered. A memorable museum preserves monumental sculptures and mosaics – a melange of classical culture, from fauns, funerary steles, huntsmen on the trail of fabulous beasts, satyrs and river deities, to a serpent-encumbered man (possibly Laocoon) and a massive bull’s head still so full of force it might be about to burst from the wall.

The theatre, which was built around 15 BC and seated 6,000 spectators, is the most striking structure, with its fantastically well-preserved first century AD façade of two tiers of Corinthian columns, with statues of gods. The more downmarket neighbouring amphitheatre was used for gladiatorial contests and held 14,000. Standing in its ring amid the great silence of Spain’s high summer, it is difficult to visualise such violence, to think of those thousands of tense or shouting voyeurs, to think of this sand spattered with gobbets of gore. Yet real men, pumped with adrenalin or in a state of terror, once had to run down these now largely unroofed walkways and blinking out into the sun, amid the bloodthirsty roaring of the town, to kill others who had done them no harm, or transfix bristling but terrified beasts from boars to Barbary lions.

More pacific thirsts could be slaked by waters brought from several miles north, along the city’s second greatest landmark – the 1st– 3rd century Milagros aqueduct. The 2,700-foot-long structure is one of the most intact of all aqueducts, its double deck arched outline proudly emblazoned on tourist ware, and attractive to nesting storks. Nearby is the 60-arched bridge over the Guadiana, at 2,600 feet one of the longest of surviving Roman spans.

Oblivious to architectural distinctions, the Guadiana flows on to the handsome if obscure town of Olivenza, whose chief claim to national fame is as having been a Portuguese possession between 1297 and 1801. In that latter year, French and Spanish troops invaded Portugal to prevent it supporting Britain, and the Spanish commander plucked oranges as trophies to send back to the queen (reputedly his lover), which has resulted in it being called the ‘War of the Oranges.’ The Spanish kept all the territory they took on the east bank of the river, although the Portuguese government’s official position even now is irredentist. The sundered nature of the area is emblematized by the late medieval Ajuda bridge on the road to the Portuguese town of Elvas, destroyed in 1709 during the War of the Spanish Succession, and never rebuilt. When we swam in the Guadiana’s opaquely green waters one evening, we were floating in international legal limbo.

Hispanicization programmes pursued by Spanish governments from the Bourbons to the Francoists are now being quietly dropped, with renewed interest in the area’s Portuguese heritage symbolised in bilingual street signs, and Portuguese nationals in the area permitted to vote in Portuguese elections. Olivenza’s best known son is probably Paulo da Gama, older brother of Vasco da Gama, who commanded one of the ships of Vasco’s fleet on the famous 1497 voyage to India, which opened up the sea route from Europe to the East by way of the Cape of Good Hope. Deep roots and spreading branches are to be found even in Olivenza, and could be symbolized by the unique Jesse Tree carving in the town’s chief church – at 45 feet tall probably the world’s largest, and filled with rich fruits.

Cáceres has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1986, and its intact medieval Ciudad Monumental attracts film-makers, most recently those responsible for Game of Thrones. But medieval artefacts seem almost modern when compared with the prehistoric hand-prints in the close-by Cave of Maltravieso, at more than 67,000 years old the oldest known anywhere. Crude Celtiberian figures in the city museum speak of stories told and forgotten before the Romans were heard of – who got here as ‘late’ as 25 BC.

Pigeons and crows rise with a sudden flapping and fly in flocks across the otherwise deserted Plaza Mayor, their shadows accompanying them companionably across the cobbles, clearly outlined by the hardness of the light. The Cáceran cityscape suggests massy strength, with its parapeted towers and turrets of convents and grand houses, red-brick or limestone or white stucco, red-roofed and almost completely lacking vegetation. Rare windows look onto worn stone steps and burning back-alleys where every tall wall or gateway or church pavement may carry vaunting coats-of-arms of caballeros once militant in faith and family pride. Bears, castles, crosses, eagles, putti, swords and suns are everywhere in evidence – armorial cliches, but still suggesting strength as well as melancholy.

Carvings seen in Cácere’s churches are sometimes stranger, from the archway graffiti of centuries ago choristers (as artless as the hands of Maltravieso), to a rampant lion with an inconveniently erect penis, beset by snarling disembodied dogs’ heads. In one hushed interior is a startlingly sable Jesus close to a preternaturally pale one of alabaster, whose fine blue cracks could almost be the ‘blue blood’ once so prized by hidalgos.

Hidalgos were often also conquistadores, like Vasco Núñez de Balboa. His statue is one of the first things you see on entering his birthplace of Jerez de los Caballeros – although the caballeros in this case were the Templars, whose town this was. The Jerez of today is deathly still even by Spanish summer standards, at the junction of unimportant roads in a landscape as bereft of people as it is full of toponymic significance, with place-names referencing the nearby frontier with Portugal, as well as spiritual frontiers, on the boundaries of reality and reason – Eremita de Nuestra Senora de los Santos, Convento de Rocamador, Salvatierra de los Barros, Valle de Santa Ana, and the ominously evocative Valle de Matamoros (‘Valley of the Moor-Slayer’).

Balboa came from the lower nobility, a class often fiercely proud of their descent, but rarely rich. In 1500, he joined in an exploratory voyage to present-day Colombia. He tried farming in Hispaniola but failed, escaping creditors by stowing away back to Colombia, and then moving to Darién in present-day Panama. Here with a few others, he founded Santa Maria de le Antigua, the first permanent European settlement in all the Americas, and began to grow rich by barter or war with the local tribes. By 1511, he was Darién’s governor and captain general. He organized expeditions into the interior in search of gold and slaves, often using brutal methods, such as torture or using dogs to tear enemies to pieces.

Hearing folk-tales of a fabulously wealthy kingdom somewhere to the south, governed by an emperor who was initiated in gold (“El Hombre Dorado”), Balboa requested reinforcements, but although these were forthcoming, enemies at court ensured he was not given command. He started out without them, and in September 1513, standing with “wild surmise / silent, upon a peak in Darién,” (as Keats described the moment famously, although giving the credit erroneously to Cortés) was the first European to see the Pacific, which he promptly claimed for Spain. He was restored to royal favour, and named governor of this exciting new sea, and of Panama.

But rivals continued to intrigue against him, even as he persisted in his exploratory endeavours – in 1517/8, masterminding the transportation of a fleet of ships overland across the isthmus in pieces, to explore the Gulf of San Miguel (1517–18). In 1518, he was summoned home to Spain, whereupon he was indicted on trumped-up charges of rebellion and treason, and executed in January 1519.

Not content with birthing one restless spirit, this little town also gave rise to Hernando de Soto, the first European to penetrate deep into the territory of the modern United States, and the first to encounter the Mississippi River.

De Soto’s father wanted him to be a lawyer, but when Hernando was still a teenager he informed his father he wanted to be an explorer instead, and left for the New World in 1514. He prospered in Panama through daring and slaving, and came to control the area we now know as Nicaragua. Tiring of 16th century respectability, harum-scarum Hernando loaned Pizzaro two ships and sailed with him to Peru as his captain of horse. He was instrumental in the Incas’ downfall, but thereafter fell out with the less gentlemanly Pizarro, and returned to Spain.

Jerez must have seemed terribly limiting after such expansive experiences, although he dutifully endowed a chapel in the town’s church. Unsurprisingly soon he was back across the Atlantic, as governor of Cuba, with added extravagant royal remits – to conquer what we now call Florida, and explore modern Ecuador, plus special rights to whatever riches he could find along the Amazon. Seen from today’s perspective, it all seems like a fever dream, which makes it rather appropriate that de Soto should have died from that cause in 1543, in the hut of an Indian chief, about as far from parched Extremadura as it was possible to get in the 16th century. Many today would probably argue both men should have stayed in Jerez.

Cordoba rose to eminence in the second century BC, as the Romans’ Corduba, the capital of Hispania Ulterior. It supported Pompey, and was accordingly destroyed by Caesar, but rebuilt itself to become capital of the new province of Hispania Baetica. Lucan was born here in the first century AD, nephew of his fellow Corduban, Seneca the Younger. After the Moors conquered the area, Cordoba became a cultural and political powerhouse, one of the three chief cities in the Muslim world (after Baghdad and Cairo). In the 12th century, it was the birthplace of both the Muslim polymath (and pioneering interpreter of Aristotle) Averroës, and the Jewish philosopher Maimónides, although the latter had to leave Spain after refusing to convert to Islam (he later became Saladin’s astronomer).

The Mezquita, Corduba’s world-renowned mosque, which is now the city’s cathedral, was begun (and finished!) in 785. The ingenious architect economically re-used columns from the former Visigothic cathedral, and close examination of capitals reveals some ‘un-Islamic’ figurative carvings, including a demon, a monk and a bare-breasted woman. The Mezquita was originally open along one side, but that side was bricked up after conversion to cathedral, leaving a rather crepuscular interior.

A forest of columns, in a variety of handsome stones, stretches away in all directions, all made uniform in height and given aesthetic unity by alternating light stone and red brick in tiger-striped arches. Even crowded with tourists, the effect is very impressive, its stripped-down simplicity clearly designed to induce a state of raptness.

In the gardens of the old Alcazar, there is a statue showing Columbus meeting Fernando and Isabella here in 1486, and other kingly or classical sculptures define lines of sight, or stand at the tops of steps. Clipped cypresses give shade for shrill cicadas, and carp cluster in the warm baths of rectangular pools. Some of the prisoners of the Inquisition, which used the Alcazar buildings between the 16th and 19th centuries, could probably get tantalizing glimpses of the gleaming garden, although by the 19th century the whole town had become shabbily poor. Those sad buildings remained in use as a prison into the 1950s, but now shelter instead tremendous Roman mosaics, evidence of Augustan glory days.

Battling through thick undergrowth along the banks of the Guadalquivir, I looked out for snakes, but happily only disturbed ducks, egrets, and a frog, which hopped disgustedly away as I approached – a pleasingly amphibian touch for so dry a land. Another amphibian landmark then loomed into view – the reconstructed and seized-up Albolafia waterwheel, the last of many to whirl in these waters, grinding grain and pumping water for the Alcazar. Ungrateful Isabella found it too noisy, and demanded it be disabled during her stays – a circumstance demanding Tarot metaphors about Wheels of Fortune and a Queen of Swords.

I stepped outside Spain, to be greeted with a breezy “Good morning, sir!” by a burly West Midlander policeman. This is another of Spain’s disputed borders – the airport runway that both bridges and divides Spain from Gibraltar. Hundreds of tourists were streaming over from the Spanish side to sample the anomalous state of the Rock, so geographically Spanish, so culturally caught in a hard place.

This has often been a controversial frontier, as befits so unignorable and strategic a promontory – for ancient heroes, one of the limits of the known world, and even for moderns, a key to the Mediterranean. Even before the ancients, there were heavy-browed hominids here, who left their skulls for us to find – in 1848, the first adult Neanderthal skull ever discovered. Joint ancestors of ours still reside here – the several hundred Barbary macaques on the upper reaches of the Rock, which grab food and gurn and publicly clean their private parts to delight and disconcert visitors.

The duty-free shops for which Gibraltar is renowned seem like excrescences when seen against the massive ruggedness of the Rock, its notorious egg-and-chips and British newspapers more than usually unpalatable. But such are inevitable accompaniments to long British expatriate presence since its capture in 1704 – flavours of home for old-time sailors and soldiers and modern financial consultants alike.

Other British traces are pleasingly Ruritanian – a neat little courthouse, the Governor’s mansion, a modest cathedral, seat of the delightfully named Bishop in Europe, and Union flags everywhere. But there is seriousness here too, the colony a source of invisible earnings through taxation and e-gaming, a centre for ship repair and real wargaming and, not least, a psychological salve for British bad feelings about a century of ineluctable decline.

The mariners in the Trafalgar Cemetery would have scarcely understood this busy pleasure-seeking Gibraltar, which in their day must often have felt Godforsaken, a limit to their known world. They nevertheless defended it resolutely, right from the start when the Spaniards tried to take it back; on one occasion in late 1704, the whole defence rested on just 19 marines and one officer in one redoubt, who somehow held on as their numbers were whittled down to six. Generations of British army engineers since have used their service-time shrewdly to mine the monolith with batteries, emplacements, roads, stores, tunnels and walls to deter potential retakers.

Naval frigates still call here, but now most shipping is pacific – cruise liners and yachts, and far more importantly, cargo vessels beating up or down the Inner Sea for Suez or Atlantic. Africa beckons beyond those storied Straits, almost within swimming distance, a blue coast once of legendary danger, but now just bad conscience for well-fed Westerners eating ice-creams at Europa Point.

The close-at-hand Catholic Shrine of Our Lady of Europe is in a fairly modern building, earlier incarnations having been sacked more than once. But it contains a fortunate 15th century wooden icon, a Virgin and Child so venerated the Shrine would be saluted by ships – except those of the English in 1704, who looted all the silverware and threw the decapitated icon into the sea. The pieces were fortunately found by a fisherman, who gave them to a priest. The statue was kept across the bay at Algeciras until 1864, when it was returned to the Rock, although unrestored until 1997. In 2009, Benedict XVI gave the much-tried Shrine a much-coveted (and surely deserved) Golden Rose.

We came back to Seville with the days ticking down, and too much still unseen, or unseeable. But there was time, just, for some secular shrines – shrines like the Palacio Lebrija. The countess who bought the 16th century house in 1900 was an inveterate collector, lucky enough to live before laws were brought in to protect historic sites. Perhaps the collected items were also ‘lucky,’ because they could have been scattered or destroyed by less appreciative discoverers.

Countess Lebrija lavished prodigious pesetas on antiquarian and artistic loves, making her house a salon for the most cultivated sevillanos, floored with mosaics from Itálica, remaking rooms to fit their floors rather than the other way around. She ransacked her own ancestral home too, removing hundreds of 18th century tiles from her country place, to give her sophisticated town interiors charmingly naïve rustic verticals. There are affectionate caricatures of countryfolk in the fashions of 250 years ago, got down with rapid strokes by journeymen painters – farms slumber on vanished afternoons, hunters pursue the hart, and hounds harry hares – glimpses of a Spain disappearing even in 1900.

The Palacio de las Dueñas is the Seville home of the Dukes of Alba, one of Spain’s oldest grandee families, prominent since the 12th century. The Dukes of Alba are descended from James II of England, and the family name Stuart recurs in their history. Behind the bougainvillea which blankets the façade are peaceful patios leading off state rooms holding an art collection dominated by 16th and 17th century Italian painters. There is also a later, uglier collection of bull-fighting ephemera, ranging from naive 19th century oils to lurid 20th century posters and the stuffed heads of rare bulls that wreaked revenge on their tormentors.

Antonio Machado was born at the Palace in 1875, son of the Palace caretaker. Antonio would become a Modernist poet, friendly with Verlaine and Wilde, earning a reputation for evocations of lost places and overgrown gardens. On a plaque on the Palace front is an extract from one of his poems: “This light of Seville … is the palace / where I was born with his rumour of fountain. / My childhood are memories of a patio /and a bright potager where the lemon tree ripens.” The lemons are luckily still there – and even more flavoursome, the chapel where Amerigo Vespucci may have married.

On our last evening, we found ourselves by ‘chance’ eating outside the oldest tavern in Spain, Las Escobas (The Brooms), close to the Cathedral – so named in allusion to a local broom-maker whose manufactures were bought by a whimsical former landlord to be stuck on the tavern ceiling.

A more famous habitue is said to have been Cervantes, who came to Seville in 1587 in search of work, and would stay there until around 1600. He applied several times to go to the New World, but was turned down, rather unsurprisingly, as his left arm had been rendered useless at the Battle of Lepanto. He had also spent almost five years as a slave, so could hardly be described as an optimal employee.

He found less exciting employment in Seville as a government agent, collecting produce for the ill-fated Armada. He was equally ill-fated, or maybe worse, in a later job collecting taxes, and spent some time in the prison at Seville. Don Quixote was almost certainly written elsewhere, but Cervantes’ experience of Seville’s seamier side did inspire his ‘Exemplary Novels. Rinconete and Cortadillo tells of Seville’s thieving fraternity, and Dialogue of the Dogs of the city’s slaughterhouses.

We sank a sangria to Spain’s greatest writer, and this captivating and connected city – and watched our bags and wallets, and regaled ourselves on meats, as the clangour of Cathedral bells echoed down the streets.

All photos by the author

DEREK TURNER is the editor of The Brazen Head, as well as a novelist (A Modern Journey, Displacement, and Sea Changes) and widely-published reviewer. His first non-fiction book, Edge of England: Landfall in Lincolnshire, was published June 2022. Some of his writing may be found at www.derek-turner.com He is also on X – @derekturner1964