The story so far (Chapters 2-8 inclusive have all previously been published on this site, starting here). The complete poem has just been published as A Man of Heart, by Shearsman.

Mid 5th century Britain. After the legions have withdrawn, the island is facing civil war, a growing number of external enemies and a steady tide of pagan migrants looking for land.

Vortigern has been appointed to protect what’s left of Roman Britain. The precarious balance of power he had established has been destroyed by a British revolt, led by his son. He retreats towards the hills with his wife and the remainder of the Field army.

At this point, the late 12th century narrative I’m following slides into a different version of the past, and any connection with History as understood in the 21st century is lost.

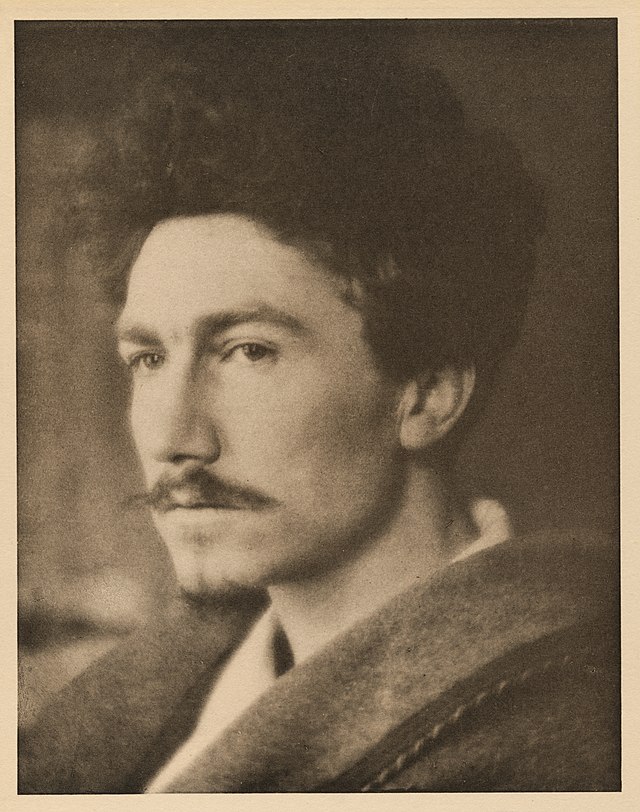

LIAM GUILAR‘s continues his epic of post-Roman Britain

The Hunt for Merlin

Vortigern, his wife and retinue

have retreated to the green hills

with the grey mountains at their back.

The wizards tell him where to build.

Each day the workmen sweat to raise a wall;

during the night the walls collapse.

(Seven times, not three as you’d expect).

The wise-men mumble together then announce

they need the blood of a fatherless boy.[i]

Find him, they thunder, sprinkle his blood

and your fortress will be impregnable.

Rowena, astonished by stone buildings,

seeing magic in the masons’ every move,

understands the fact of sorcery.

Vortigern, patient, muses:

four centuries of Roman stone

and now we cannot build a wall?

He sends men hunting down the hill

into the wooded valleys.

In the unmeasured space between

an end and a beginning, along a ridge,

scraped drop on either side, to the summit.

Looked down at broken clouds, across to distant,

unknown, crumpled peaks. The valley;

inept geometry of distant fields,

a path falling off the ridge towards the track

that followed the scrawl of infant river.

Companions wearing mail,

thick woollen cloaks, dark red,

held at the shoulder with an ornate brooch,

only their eyes visible in the helmet’s gilded face,

reading the boundaries, a line of trees,

a stream, a standing stone.

Saw the rustler’s pathway peeling off the ridge

to meet the hammered track

leading to the cluster of round huts,

pointed roofs and sagging thatch,

fenced space, the drift of smoke.

The perfectly ordinary settlement.

Entering the village, they walk into a silence

abrupt as the chill slap of a breaking wave.

No child is playing. No woman singing at her work.

Painted figures, fading on the grey wall of the cloud.

No one runs away, or screams, or sounds alarum.

No one is reaching for an axe. They stop.

They watch. They follow, herding the strangers towards

the largest hut, white walls blotched

beneath the inept cone of sagging thatch.

The chieftain waits to greet them,

wrapped in a bear skin, the skull as hood.

The messengers stop to admire the skin,

trying to frame a compliment.

The old man nodded. ‘Old ways.

My dad took me down into the trees.

Gave me a spear, said, good luck son.

Come back with a bear skin or don’t come back.’

They step into the hut.

‘You have come for the child.

He says you will take him to his woman.’

Behind the fire, in the gloom,

a dark stain, small and indistinct.

Something catching the light flicks,

golden. ‘Do not deny your mission.

He knows what happened, what will happen’

-The shape moved, seemed larger-

‘could happen.’

This man, who as a child

went after bear, alone,

armed only with a spear,

is terrified.

A girl came to the entrance.

The boy stood up and left with her.

‘I have sent word to his mother.

She will travel to the King.

We have sheltered the abomination

and in return, he has shown us what we are.

True, he has given us dominion

over the peoples of the valley.

He has kept our cattle healthy,

our crops abundant. Terrified,

our neighbours pay us tribute,

sacrifice their daughters to his lust,

give us gold and precious things

from places far beyond

the eastern limit of the Empire.

Glass bowls, jewelled cups,

silk filigreed with gold.

At first we gloated over our success,

and wallowed in the excess of desire.

But then we realised the price we paid.

We have done foul things at his bidding.

But we have seen him part the clouds,

make running water turn to ice in summer.

He has raised a hand and brought down hail,

fist sized, to smash our enemies

and ten feet from them not one of us was touched.

We have done too much to keep him happy.’

Outside someone was sobbing.

‘You are the King’s men.

That makes you loyal and brave.

You stayed when all the others ran.

Take the boy to Vortigern the King

He rarely speaks, he seldom asks…’

The old man’s voice was melting.

‘I would rather face a bear again,

with only these old hands,

than risk the anger of that child.

But warn your King, tell him: take care.

The child will give him anything he wants

but his price will be beyond imagining.

When news spreads that he is gone

our enemies will devastate this village,

take not one slave, touch not one woman.

They will kill everyone and then

erase this stinking cess pit from the landscape.

When they arrive, we shall not fight.

Death will bring a fine forgetting.’

The villagers gathered in the fog,

the women clutching their children,

like failed approximations of the living.

The men stranded in poses of dejection.

The chieftain led them along the path

towards the rising hills. As the ground

sloped steeply upwards he left them.

‘You will need a week to reach your King.

By then, if your mind is still intact,

you will believe everything I’ve said.’

On the first day,

they followed the track upstream to the ridge

in fog so thick they never saw the sun.

The boy did not speak.

He didn’t greet them in the morning,

nor wish them well at night.

On the second day they picked their way downstream,

the slopes of scree like broken shards of fog,

scattered in shining fields that clattered away downhill.

On the third day he said;

‘We will go no further in this valley.

My enemies are waiting.

We must climb that ridge.

On the other side is a village,

where there are horses.

You will kill their owners,

then you will take me to my woman.’

Vortigern had trained them well.

Their plan was clear and simple.

Entering the settlement, first

they would ask for horses

in the King’s name. Then

they would offer to pay.

If this was refused, then,

and only then, the killing would begin.

The boy had other plans.

Eyes closed, swaying, lips mumble,

hands move, an unexpected squall

drives rain against the window

and blurs a clear view. Or on high ground

the clouds move in so fast the outlines disappear

and there’s only vagueness and sudden dark.

Swinging axe and stabbing spear,

cutting through to the surprise

of scattered bodies, bloodied edge.

They were saddling the horses.

‘Where is the boy?’

‘With the women.’

‘I thought we killed them all?’

‘We did.’

There was the rain

and somewhere was the night.

Each man huddled in his own cloak

and endured the darkness

until the boy made a pile of sticks.

A movement of his hands, a black flame,

tinged silver at the edges,

sprang upward like an army

leaping from its place of ambush.

They huddled closer. No light,

but their sodden cloaks began to steam,

their frozen hands unclenched.

The wood was not consumed.

The escort saw the landscape

as passage, difficult or easy;

shelter, safety, risk. The boy?

Scree was the outrider of his enemies,

the scattered boulders sentries for his army,

waiting for the signal to advance.

Only the water was patron and friend,

escorting him towards his woman.

In the woods their passage slowed.

He must greet every tree he passed,

laying his palms flat on each trunk,

lips moving to shape words no one recognized.

If no blossom sprang beneath his hands

that was worse than the making of fire.

3. Merlin’s Mother

Care has worn her face into perfected sorrow.

But even in the habit of a nun,[ii]

she is sensuality incarnate,

a delirious possibility of carnal bliss.

‘Tell me lady, who is the father of this child?’

‘I am a King’s daughter, Conan was his name,

before the Saxon’s came, before they killed him.

I do not know the father of this child.’

‘You were raped? No? So tell me, lady,

tell me, how did you get this child?’

Rowena wraps her cloak around the sobbing woman,

leads her away from the armoured men,

settles down to listen, seeing images.

…summer flies in clouds above the shattered brightness of the pool.

Girl children playing: armoured guards like dirty statues in the shade

along the rocky shore.

‘Beneath my father’s palace a stream snaked between the trees

and upstream of where it cut the path leading from the fort

our childish secret place, a spring running from a carved grey stone,

with swirling snakes coiling around an open mouth

and a broken headless statue.

(We blushed the first time that we saw it, erect, enormous.

Imagine that? And other silly chatter).

My slave girl trying to be important,

told us pagans worshipped this forest god, this half-man, half-goat,

and if a maiden, toying with herself, close to this place of power,

spoke his name three times, he would appear and pleasure her.

No one believed her rubbish.

We were children,

girls in their white shifts splashing in a pool,

drifting through the summer heat.

A long hot summer.

Maybe five years after we had found the stone.

The river shrivelled to a chain of stagnant ponds.

Unmarried, un-promised

with maids to the river bank.

Tents in the shade of the trees.

Guards? Of course.

On the hottest night,

aware of sweat beading and running

like grazing insects,

aware of my own body,

humming its lust.

Images of a future husband,

a constriction in the throat,

the heat became intense.

I murmured the god’s name,

opened my eyes to the golden man,

the carving of Priapus come to life.

His eyes blazed golden in the shade.

The frost burn of pleasure.

All night delirium, the rhythms of flesh,

exhausted, weeping with delight, I fell asleep.

In the morning, in the river, trails of blood,

signs of the night’s excesses

but no signs anyone had slipped into my tent.

That afternoon I dreamt

church doors were shut against me.

I saw the priest and congregations

stone a woman in the field

and knew that she was me.

But until the Golden Man returned,

my body crooned for him.

My mind a swamp of images of what we’d done.

3 nights the Golden Man appeared and played with me.

3 nights of ecstasy I’ll never know again.

Then no more.

I prayed for him. I prayed to him, but the nights were a rack

and I despised the sunrise confirming that he had not come.

I sickened. After three days, my clothes were tight

and food was hateful to me.

In three weeks I gave birth:

a child with golden eyes.

As they laid it on my breast,

he smiled at me and said:

‘Daddy sends you greetings

You will not meet again.’

And that lady is how I got my child.

Must I stay ‘til it arrives?’

‘You fear your own son?’

‘Speaking his crimes would rot my mouth.

Remembering them is penance enough.’

Rowena let her go.

Vortigern asks: ‘Is it believable?

She wouldn’t be the first maid

who snuck away to meet her lover

and then made up such a story

when she found out she was pregnant.’

‘No. Her fear is genuine.

Whatever he did is so foul she won’t speak it.’

4. A Fatherless Boy

The messengers, staggering,

bring the boy before the King.

Like a dead bird on a wire

animated by the breeze,

a stain gaining definition

as it strikes, the boy,

brushing aside the soothsayers,

swooping towards Rowena.

‘Blessed is the well below the valley.’

He strokes her breast. She recoils,

hands tying invisible knots, speaking

words that no one present understands.

The boy stumbles, recovers, laughs,

brushing flies from his face.

Reluctantly, he turns to Vortigern.

An old man’s voice,

with rust at its edges

and rot at its core.

‘I have loosed the bands of Orion.

I can summon leviathan.

He will make a covenant with me.

I have gone down to hell

and freed the rider in the clouds.

When he’s enthroned upon his mountain

he will bow before me as my slave.

I can harness the unicorn to the plough.

I can make you Emperor.’

‘Of what?

The Empire’s gone.’

‘It can be rebuilt.

For you.

For a price.’

‘And you want my soul?’

‘I wouldn’t wipe my arse on it.

I want your wife.’

Vortigern hears Rowena hiss,

senses she has stepped back,

holding seax in a steady hand.

‘She doesn’t want you.’

‘Look fool!’ Vortigern sees his province,

refined to a detailed map.

To the south, the shrinking stain

of Vortimer’s rabble and across the Channel,

the scum filled puddle of The Boys’ growing horde.

The black plague of uncountable ships,

swarm the coast, or burrow up river

like maggots attacking a corpse.

‘Give me your wife.

I will annihilate your enemies.

I will be a tempest in a field of corn.

The plans that they have nurtured,

their dreams and ambitions, I will ruin

as they watch, like patient farmers

as hail destroys their crops,

announcing their starvation.

Give me your wife.’

‘Child, she is not mine to give.’

Time thickens like a river freezing.

There is only the voice;

a wind from nowhere,

and the images of burning homes,

pestilence, atrocities, famine.

Vortigern sees his kingdom.

The dead lie where they fell,

crops rotting in the fields,

the starving cattle wander free.

He could see misery,

surging over the land and drowning it.

‘I can put an end to this.

That’s what you want;

peace, order, stability.

Give me your wife.’

He sees himself in gold embroidered silk,

seated on a marble throne,

in a many columned hall.

The cities flourishing again,

merchants on the roads,

ships safe in the harbour. He hears

the grateful people speak his name.

No enemies, assassins

outrage or complaints?

This time, he laughs.

The ice breaks.

The river moves.

‘Child, this is not yours to give.

There will always be wars. Always

people who starve while others feast.’

‘You will die alone.

The sky will rain fire.

You will be vilified

for eternity unless

you give me your wife.

They will debate your name

and your existence.

Your life will be obscure,

your death will be unknown

unless you give me your wife.

She is blessed amongst women.

The fruit of her womb will be the Messiah:

a Warrior King to end the Saxon threat,

reconquer Rome and found a Reich

to last a thousand years.

His name will never be forgotten.

Nor will mine.’

‘Child, she is not mine to give.’

Vortigern dwarves the chubby boy;

a foul vagueness slithered from a cave,

shrivelling in the unaccustomed light.

‘Go your way.

Take this gold,

my thanks

for the lesson.’

‘We will not meet again,

Vortigern Dead King.

I could have saved you.’

‘No,’ he says,

with the conviction of a rock.

‘No, you could not.’

5. The end of the province of Britannia

Morning, and the mist filling the valley below,

clouds streaking the sky like smoke plumes

streaming from the distant peaks. The sun

cold, bright and ruthlessly indifferent.

His officers accumulate around the wagon.

A baffled Rowena stands beside him,

leaning into whatever happens next.

The remnants of Britannia’s last Field Army.

Faces he remembers from the day they left for Lincoln[iii].

He knows them all; their families, their stories,

which one can improvise, who imitates a wall,

who plays it safe, who takes a chance.

‘Some of you are angry. Some feel betrayed.

You think you would have danced

to your crucifixion if a comrade could be saved.

We have all lost friends who gave their lives

so we could live. You think I’m selfish

because I wouldn’t trade this woman to a child

to save the province.’ He heaved a sack towards them.

‘There is all the coin that’s left.’ He threw a second,

two malignant lumps shifting as they settled.

‘And there’s the plunder; gold rings, armbands, torques…’

the list is endless and irrelevant, dismissively

he waves his hand towards the chests beside him.

‘The royal treasury. The province. Britannia.

That’s all that’s left of what we swore to serve.

But what we swore to serve

meant so much more than that.

I will not sacrifice another life

for two bags full of shiny trash.

Divide it now amongst yourselves.

See that no man feels aggrieved.

Those who wish to leave: go home.

Or you can take an oath to follow me.

I will not ask you to do anything

I have not asked before,

but I will make you rich,

and give you lands for your old age.’

The sound of swords being drawn,

the rustle of kneeling men.

Later she finds him, on a fallen trunk.

The twisted branches of the stubborn trees

behind him like a web the boy had spun

to trap a king.

‘You are a strange man, Vortigern Cyning.

Locrin locked a woman up and lost his kingdom.

You risked the loss of yours to set one free.

The two sacks are untouched in the grass

and not one man has left.’

‘We’ve clung to the old titles;

adepts of a failed dispensation,

whose rites and formulas

belong to history, repeating

an incantation that’s familiar,

habitual, comforting,

when it’s obvious the gods

have long since left the temple

and the words no longer work.

It’s a strange new world

we’re stepping into;

clean, cruel and honest.

At least until we discover

new reasons for hypocrisy.’

[i] Laȝamon describes this advice as ‘leasing’ (lies.) The shift from bishops and priests to wise men and soothsayers is in his text.

[ii] Another one of Laȝamon’s anachronisms. The story of Merlin’s birth and conception follows his version.

[iii] See chapter 4

More information about Laȝamon’s world and work, as well as the two published volumes in this project can be found at www.liamguilar.com

LIAM GUILAR is Poetry Editor of the Brazen Head