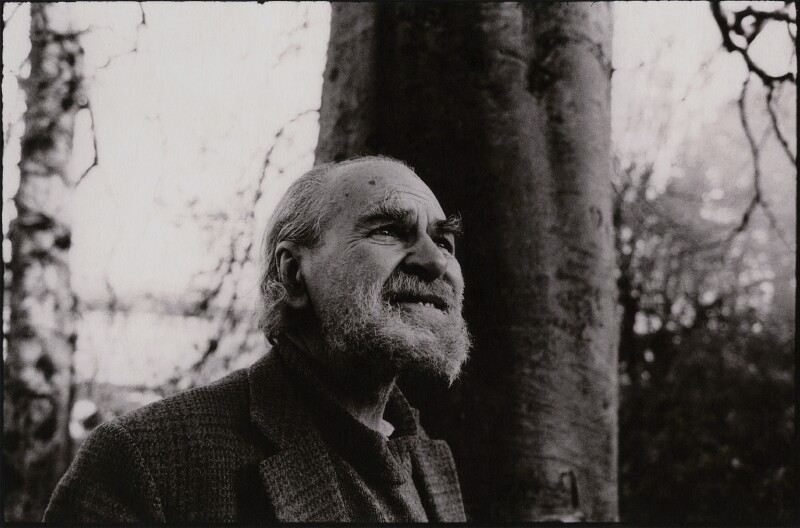

Letters of Basil Bunting

Selected and edited by Alex Niven, Oxford University Press, 2022, £35

LIAM GUILAR welcomes new insights into a little-studied modernist’s mind

Basil Bunting died in 1985. Despite having been praised as one of the twentieth century’s ‘greatest poets’ critical attention to his work has been rare. A reliable biography didn’t appear until the publication of Richard Burton’s A Strong Song Tows Us in2013; an annotated collected poems, edited by Don Share, not until 2016. Now, with the publication of Alex Niven’s much anticipated edition of Bunting’s correspondence, it’s possible to eavesdrop on one of the twentieth century’s most interesting conversations about poetry[i].

In his eighties, Bunting looked back on his life:

Once upon a time I was a poet; not a very industrious one, not at all an influential one; unread and almost unheard of, but good enough in a small way to interest my friends, whose names have become familiar: Pound and Zukofsky first, Carlos-Williams, Hugh MacDairmid, David Jones, few indeed, but enough to make me think my work was not wasted.[ii]

If you recognise the names of his friends, that ‘good enough in a small way’ is an excellent example of the English art of understatement. But it’s not a popular list and despite the excellence of his poems, Bunting remains a marginal figure. No one reviewing the letters of T. S. Eliot needs to explain who T. S. Eliot was, or why he is of interest.

The life

Born in 1900, Bunting was imprisoned as a conscientious objector immediately after leaving his Quaker school in 1918. He studied economics before drifting to Paris where he met Ezra Pound and worked, alongside Ernest Hemingway, for Ford Madox Ford. Following Pound to Italy, he met W.B. Yeats and Louis Zukofsky in Rapallo and began a life-long and life altering affair with Persian literature.

His first published poem, Villon, is one of the finest long poems of the 1920s[iii], but by the end of the 1930s Bunting’s career as a poet had stalled: his first marriage had failed, he was out of work and separated from his children. The war rescued him. He discovered he had skills that others valued. He rose through the ranks to Squadron Leader, worked for British Intelligence, then after the war, returned to Persia, first as a diplomat, before resigning to marry a Persian and becoming the Persian correspondent for The Times.

Expelled from Persia and then unceremoniously dumped by The Times, he struggled to find work in post war Britain.

Despite the excellence of his poems, the story could have ended here, with Bunting as a footnote in histories of literary modernism, remembered as one of Pound’s ‘more savage disciples’[iv], but in his sixties, spurred on by his meeting with a young Tom Pickard, he wrote Briggflatts; at 700 lines a short long poem, praised as the ‘finest’, ‘greatest’ or ‘most important’ long poem either of the twentieth century or ‘since The Wasteland’. He enjoyed a brief period as ‘Britain’s greatest living poet’ before fading away in a series of university jobs and poetry readings.

Poetry

From such a long and varied, life Niven estimates only about 800 letters have survived, of which approximately 600 relate to Briggflatts and the period after its publication. He has selected almost two hundred and thankfully decided to print complete letters rather than extracts.

Divided into three sections, the bulk of the book is devoted to the 1960s and afterwards. For anyone interested in poetry, rather than Bunting’s biography, the core of the book may be the pre-1960s letters to Pound and Zukofsky.

Briggflatts was praised by critics of the stature of Hugh Kenner and Donald Davie and poets as diverse as Thom Gunn, Allen Ginsberg and George Oppen, but Bunting’s status in the critical hierarchy has never been secure.

Perhaps his version of poetry is too austere to be popular. In a letter to Poetry Chicago (not printed by Niven), he wrote:

We are experts on nothing but arrangements and patterns of vowels and consonants, and every time we shout about something else we increase the contempt the public has for us. We are entitled to the same voice as anybody else with the vote. To claim more is arrogant.[v]

Throughout these letters and in later interviews he repeatedly stated the belief that politics, philosophy and theory harm poetry. The poet’s job is to write good poems.

What I have tried to do is to make something that can stand by itself and last a little while without having to be propped by metaphysics or ideology or anything from outside itself, something that might give people pleasure without nagging them to pay their dues to the party or say their prayers, without implying the stifling deference so many people in this country still show to a Cambridge degree or a Kensington accent. [vi]

It’s possible to go through these letters and compile a list of quotations to show he had little time for academics or literary criticism. He was publicly dismissive of creative writing courses and poetry competitions, while working on the former and once, memorably, judging the latter. He didn’t think poems should be explained; if a poem requires footnotes it’s a failure and tying the poem to the poet is a fundamental mistake.

What characterised Bunting and his correspondents was the intense seriousness with which they applied themselves to writing. Poetry was a craft and writing it involved ‘sharp study and long toil’. The ‘study’ involved arguing into existence a standard of excellence selected from poems going back to Homer. Once tentatively established, they attempted to excel their models, supporting each other through stringent criticism.

Bunting’s criticism, shown here in his letters to Zukofsky, was not for the faint hearted, but it was driven by the belief that some poets, Pound and Zukofsky explicitly, were ‘entered without handicap against Dante and Lucretius, against Villon and Horace.’ In the same letter, he explains: ‘At least for my part, I’d rather have somebody who is thinking of Horace call my poems bloody bad than to hear them praised by somebody who is thinking of-who-Dylan Thomas?’ (p.194).

Two other reasons for Bunting’s odd position in the critical hierarchy stand out. In some quarters he is tainted by his association with Pound, especially where Pound is only known, vaguely, for his political and racial opinions. The other is the insistence that ‘All Roads lead to Briggflatts’[vii] which condemns him to the role of a minor poet who pulled off one great poem and consistently ignores the quality of the rest of his work.

The letters qualify the first of these, while Niven’s editing and commentary seem driven by the second. If there ever was a tribe of Ezra to match the tribe of Ben, with Rapallo replacing the London taverns, Bunting was always too obdurate an individual to be anyone’s acolyte. [viii].

The explosive end of the pre-war correspondence with Pound is well-known, though the full text of the letter hasn’t been available until now. What becomes obvious is that from the late 1920s and through the 1930s the letters show Bunting becoming increasingly resistant to Pound’s politics. Bunting’s repeated statements that poetry is hampered when it tangles itself in philosophy and politics became focussed in his insistence to Pound that banging on about ill-informed economic theory was a waste of Pound’s time and literary talent, although Bunting himself isn’t adverse to sharing his ‘theories’ with Pound.

Initially refusing to believe Ezra was writing for the British fascist movement, he finally reached the limits of his patience when he learnt that Pound was ‘spilling racist bile’ in his letters to Zukofsky. His angry letter to Pound ends:

I suppose if you devote yourself long enough to licking the arses of blackguards you stand a good chance of becoming a blackguard yourself. Anyway, it is hard to see how you are going to stop the rot of your mind and heart without a pretty thoroughgoing repudiation of what you have spent a lot of work on. You ought to have the courage for that; but I confess I don’t expect to see it. (p.136)[ix]

It says a lot about the robust nature of their friendship that despite this, Pound would continue attempting to promote Bunting’s poetry, and Bunting would continue to acknowledge his debts to Pound. After the war, when Pound was incarcerated in Saint Elizabeth’s hospital for the mentally ill, Bunting picked up the correspondence, encouraged by the news that a letter from Basil brightened up Ezra’s week. Pound’s letters to Bunting, by turns abusive and incoherent, didn’t put him off.

As he wrote to Zukofsky: ‘The difficulty is how to avoid being involved in the network of fallacies while profiting from his illuminate faculty for verse and enjoying his energy and kindness.’

The same problem faces everyone today: how to see beyond the politics and racism to profit from what any poet in the past had to say about poetry and learn from what he or she achieved as a poet. Bunting managed it with his two closest friends, one a communist, one a fascist. It seems an important precedent.

Anyone interested in Basil Bunting or twentieth century poetry owes Alex Niven a great debt for the time and work that must have gone into this project.

How different the picture would be if this were a complete edition of the letters, only he knows. When Jonathon Williams published a selection of his letters from Bunting, he wrote: “What a stern, serious, funny, extraordinary ‘literary’ (LETS HEAR IT FOR LITERARY) North of England person he was’ (Williams, p.252).[x] The Bunting of those letters, watching the birds and wild life in his garden, is absent from Niven’s collection, as are the descriptions of Persia that suggested to Burton that Britain lost a major travel writer to the Official Secrets Act.

The book’s sense of its reader is uneven. Niven explicitly describes a model reader who knows the outline of Bunting’s life and is not put off by occasional difficulties (p.xxvii). This model reader has a positive effect on his annotations, but seems to have been forgotten when he came to write his commentaries.

Why Niven thinks such a reader needs to be told what to think about the letters and how to interpret them, is a mystery. You buy an edition of a poet’s letters, wanting to read the poet’s words, and find a portion of the book contains the editor’s personal opinions and interpretations which you will never reread.

Based on his model reader, Niven’s annotations are usually deft and show a shrewd judgement of what this reader could be expected to know. He assumes that anyone reading these letters won’t need a gloss on Dante, Swift, Winston Churchill, or others. He is also unwilling to overload the letters with commentary, assuming, (rightly), that anyone who wants to follow Bunting’s detailed responses to Pound’s books; ABC of Reading, Guide to Kulchure, will have a copy.

In his letters, Bunting could be crudely dismissive of poets he didn’t like. It’s disappointing to see his editor join in: ‘Philip Larkin (1922-1985) hard right British poetaster and trad jazz critic.’ (n.277 p.384).

Sometimes the annotation strays a long way from objective facts: ‘It must be said that Briggflatts faintly resembles certain of [Dylan]Thomas’ work in form, subject and (marginal sense of) place’ (p.194). Briggflatts probably ‘faintly resembles’ a lot of things, but it also must be said it’s hard to imagine Bunting admiring Thomas enough to be influenced by him.

The introduction includes a clear and necessary discussion of editing methods. Whether an introduction to a selection of letters needs a dramatic retelling of the first reading of Briggflatts, or is an appropriate place for a summary and critique of existing criticism, depends on the individual reader. As I don’t agree with his evaluation of Don Share’s edition of the Collected Poems, unless ‘the book’s only major limitation’ is intended ironically, or his criticisms of Burton’s biography, and I think he misreads the Pound-Bunting disagreement over Bunting’s translations of the Shahnemeh, I’m suspicious of his statements about literary matters where he strays from simply providing factual biographical context.

He uses his introduction to stake out his version of Bunting’s life, at times in explicit opposition to other published versions. I’m not convinced this is the right place for it. His dissent from Burton’s views of the significance of Bunting’s Quakerism is pointed, but his dismissal of Burton’s biography as ‘relatively light on critical explication’ is baffling. Eager to point out that book’s ‘shortcomings’, he seems to be criticising Burton’s biography for being a biography while temporarily forgetting just how problematic and limited letters are as biographical evidence.

The trust in the reader, obvious in the annotations, is not evident in the editorial commentary running between the letters. I think there’s too much. Rather than let the letters speak for themselves, he interprets the evidence and intrudes his opinions, unnecessarily:

For all that his language and actions often fell a long way short of today’s ethical standards, Bunting certainly thought of himself as a determined anti-racist-and this letter would seem to support that view. In the context of his historical moment, Bunting’s basic philosophical views about race were, to put it mildly, considerably more progressive than Pound’s. (p. 134-135)

Comments such as this one and less lengthy interventions like ‘even if the age difference of over thirty years was problematic in more ways than one (p.140)’ seem to miss the point that adult readers are capable of coming to their own conclusions.

Sometimes the comments have nothing to do with the content of the letters: ‘There is a pressing need to apply more and deeper scrutiny to Bunting’s colonial phase than has been evident in previous scholarly and biographical treatments. But whatever its unexamined moral and political complications’ […]. (p.139)

Superfluous in terms of contextualising a letter, this manages to suggest something sinister without being informative. Even for a reader who knows the biography it’s not clear what the unexamined ‘complications’ are, or how ‘scrutinising’ them would add to the enjoyment of the poems or why or to whom such a need is ‘pressing’.

Letters encourage the tendency to tether the poems to the poet. The results of failing to distinguish between the two is a depressing characteristic of contemporary discussions of poetry, obvious in attitudes towards writers as diverse as Ezra Pound, Phillip Larkin (see above) and most recently, Dorothy Hewett[xi].

As Bunting wrote to Zukofsky:

Letters are meant to be written to affect one bloke, not a public. What is true in the context of sender and recipient may be a bloody lie in the context of author and public…secondly: the bane of the bloody age is running after remnants and fragments and rubbish heaps to avoid having to face what a man has made with deliberation and all his skill for the public’. (June 1953 qtd in Burton, page 354 Ellipsis in Burton.)

There’s nothing anyone can do to prevent that, it’s still the bane of this age, but its sad inevitability is outweighed by the opportunity to eavesdrop on one of the century’s most interesting conversations about poetry. Hopefully, Niven‘s suggestion that a complete collection of the Pound Bunting correspondence should be published will be taken up sometime soon (preferably with the letters to Zukofsky). What they had to say about poetry transcends their time, politics and personalities.

‘Long awaited’, ‘much anticipated’ and ‘ground-breaking’ are cliches of the blurb writer. For once they can all be applied honestly and accurately to Niven’s work in making these letters available. The good news is that the long wait and the anticipation have been generously rewarded.

[i] Page numbers are to Niven’s book. Richard Burton’s Biography, A Strong Song Tows Us is referred to throughout as Burton.

[ii] I transcribed this from Peter Bell’s film, Basil Bunting: An introduction to the work of a poet (1982). He seems to say something after ‘David Jones’ but I can’t understand it.

[iii] The poem was written sometime in the 1920s but first published in 1930. As Niven explains, the letters cast doubt on the standard dating and chronology of some of the poems.

[iv] The description belongs to W.B. Yeats. He surprised Bunting by reciting one of Bunting’s poems from memory when they met.

[v] Poetry, Vol. 120, No. 6 (Sep. 1972), pp. 361-365 http://www.jstor.org/stable/20595781

[vi] Another transcription, this time from a talk Bunting gave in London, in Keats’ house, in 1979. From ‘The Recordings of Basil Bunting’ with thanks to the late Richard Swigg who looked after ‘The Bunting tapes’.

[vii] Julian Stannard. Basil Bunting Writers and their work. p.88

[viii] Consigning Bunting to the role of ‘Pound’s disciple’ is to misrepresent him as badly as Tom Pickard is misrepresented when his own excellent poetic output is ignored and he’s remembered simply as the boy who midwifed Briggflatts.

[ix] Zukofsky’s response to this letter and whatever Pound had written that offended Bunting so much, can be read in Pound/Zukofsky Selected letters of Ezra Pound and Louis Zukofsky ed Barry Ahearn.

[x] Williams, Joanthan, ‘Some Jazz from the Bazz: The Bunting-Williams Letters’ in The Star you Steer By. Ed, McGonigal and Price.

[xi] For Hewett and a recent example of this problem of confusing poet and poem see the remarks in https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/apr/04/the-whole-canon-is-being-reappraised-how-the-metoo-movement-upended-australian-poetry

LIAM GUILAR is Poetry Editor of the Brazen Head