STUART MILLSON wanders imaginatively across peaceful marshes and rivers, to glimpse a world at war

Composers are not necessarily good conductors of their own works — too fussy, sometimes, or just without the conducting charisma of a professional baton-wielder, more accustomed to the stage and the adulation of an audience. Not so in the case of composer-conductor, Sir James MacMillan, a native of Scotland whose musical outlook and versatility brought such intense playing from the BBC National Orchestra of Wales in that most English of works, Vaughan Williams’s early-20th century symphonic impression, In the Fen Country.

Sir James — who as we were to find out in his new euphonium score later in the programme — has a natural feel for music which puts man in his place in the midst of a landscape where remoteness and the movements of cloud banks and sunlight over water allow your mind to wander fantastically. So the Vaughan Williams unfolded, carrying us far from Swansea’s Brangwyn Hall, like a fen-tale recounted by a local on a warm May evening (which indeed this was) — orchestra and conductor carefully finding all the threads and patterns of the lonely land so beloved by Vaughan Williams.

A similar ‘genetic heritage’ flowed into Sir James’s Where the Lugar meets the Glaisnock, a picture of the confluence of two Ayrshire rivers — part tone-poem, part euphonium concerto. Seldom has this bold solo brass instrument sounded so subtle and ‘at one’ with the soft magic of strings – the writing for the latter section of the orchestra suggesting the half-light melancholia of Vaughan Williams, but through a twenty-first century prism. At one point in the score, I picked up in MacMillan’s Ayrshire filaments of sound from distant Estonia, where a passage brought to mind the mystical, frozen-in-time style of composer, Arvo Pärt. Our solo euphonium player, David Childs, certainly gave a thrilling performance of what was a successful, deeply meaningful MacMillan world-premiere.

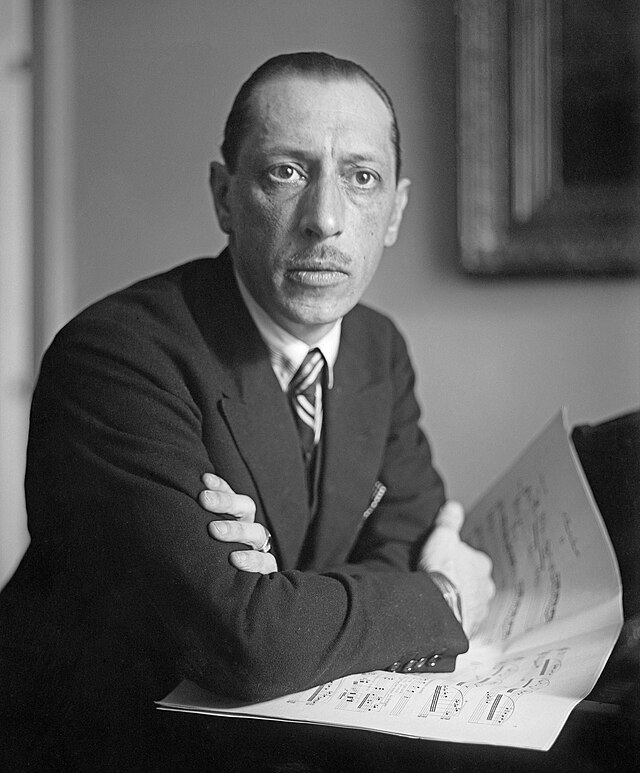

Thoughts of war (for Stravinsky, the stark image of goose-stepping machine-armies) were never far away in the composer’s emphatic, barbed, relentless Symphony in Three Movements, although the unsettling whirl of world events dispels quite uncannily in a surprising, eccentric, but warm and friendly little gavotte-like dawdle in the second movement — as if Pulcinella or Petrushka were never far away. The orchestra’s woodwind and brass produced pinpoint ‘Technicolor’ virtuosity — qualities which were centre-stage, too, in the shortish diversion (though with a clever, inventive sharpness) that is Stravinsky’s Symphonies of Wind Instruments.

The concert began with another compact and engaging mini-masterpiece, by Vaughan Williams’s composer-colleague, folk-song collector, and walking, hiking, inn-visiting friend, Gustav Holst — his Capriccio, a short work for full orchestra, with some magisterial trombone writing (Holst’s own instrument) and a foot-tapping march right in the middle of it. Yet the work seems to begin in Vaughan Williams’s fen and marsh, or the Ayrshire of MacMillan, another mysterious signpost of the continuum element in the music of these islands.

STUART MILLSON is a member of the Chartered Institute of Journalists, and a Contributing Editor to The Brazen Head